The street pictured above is Blackfriars Road in London, looking north towards Southwark tube station. The illuminated tall building on the right is Transport for London’s headquarters, Palestra House.

The street pictured above is Blackfriars Road in London, looking north towards Southwark tube station. The illuminated tall building on the right is Transport for London’s headquarters, Palestra House.

As you can see, the road is rather wide. At a rough guess, each carriageway could accommodate three cars, side by side, if not more. At least six vehicles wide.

How would we make cycling a more comfortable and pleasant experience on this road? The obvious answer would be to reallocate some of that space, and to create wide cycle tracks, protected from motor traffic, on either side. There’s plenty of room for the cycle tracks to pass behind new bus stop islands too, freeing buses and bicycles from interaction with each other. A narrower carriageway, in and of itself, would also lead to a reduction in vehicle speeds.

How would we make cycling a more comfortable and pleasant experience on this road? The obvious answer would be to reallocate some of that space, and to create wide cycle tracks, protected from motor traffic, on either side. There’s plenty of room for the cycle tracks to pass behind new bus stop islands too, freeing buses and bicycles from interaction with each other. A narrower carriageway, in and of itself, would also lead to a reduction in vehicle speeds.

Indeed, this is what the Mayor of London’s new Vision for Cycling suggests should happen on Blackfriars Road; it states that TfL

will segregate where possible, though elsewhere we will seek other ways to deliver safe and attractive cycle routes.

and

With the proviso that nothing must reduce cyclists’ right to use any road, we favour segregation

and

We will install Dutch-style full segregation on several streets without bus routes, such as the Victoria Embankment. We will install it on several streets which are wide enough to put bus stops on ‘islands’ in the carriageway

Blackfriars Road meets all these criteria. ‘Dutch-style full segregation’ is eminently possible here, despite the presence of buses and bus stops, because tracks can easily run behind those bus stops, and not interfere with the functioning of the bus route.

The problem, however, is that current guidance would not suggest the installation of tracks.

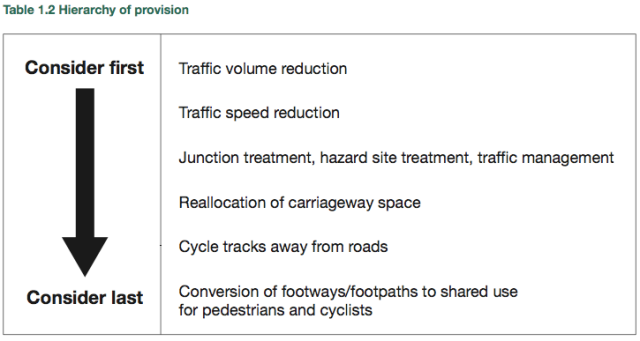

The hierarchy of solutions suggested in the Department of Transport’s Cycle Infrastructure Design (above) gets things back to front, in that it suggests last what should actually be implemented first on this kind of road. There is no need for traffic volume reduction, or speed reduction, on Blackfriars Road. The cycle tracks can and should be installed on the road, as it currently stands.

Of course, a lower speed limit of 20 mph, as compared to the current 30 mph limit, is desirable. But it is not necessary, and nor should it be considered as a priority for improving cycling conditions ahead of safe, comfortable and well-designed cycle tracks. Nor indeed do we need to ‘reduce traffic’ to make cycling a more attractive option on Blackfriars Road. (Indeed, we shouldn’t really be concerned with ‘reducing traffic’ at all, but rather with changing the mode of transport that ‘traffic’ uses).

The problem is that so much current cycling guidance is fixated on attempting to ‘reduce traffic’, when it should instead be focusing more clearly on creating good conditions for cycling. Obviously, these two aims will often overlap quite neatly, but they are not one and the same thing. I think this explains why the CTC are in a bit of a policy muddle; they have confused two different policy aims. Creating good conditions for cycling is not the same as reducing (motor) traffic, even if the latter is an outcome of the former.

Maybe this confusion on the part of the CTC stems from the legacy of the ‘no surrender’ attitude amongst their more prominent campaigners in the earlier part of the 20th century; the struggle to retain and control roads on which motor vehicles were seen as intruders still informs current attitudes. This necessarily waters down the commitment to proper Dutch-style provision for cycling, because it would require a ‘surrender’ of certain categories of road. The result is a compromise, apparent in this description of the Hierarchy of Provision provided by the CTC themselves –

Many people who don’t cycle say they’re held back by their fear of traffic, and reckon they’d cycle if there were more cycle paths away from the roads. Local demands for ‘traffic-free’ routes can be quite persuasive for councils, but when they install segregated tracks they often meet with opposition from cyclists who would prefer to cycle on the road… The dilemma over how to decide on the best option for a given location led to the development of the ‘Hierarchy of Provision’, a concept that was officially endorsed by the Department for Transport (DfT) in 1996. In theory, therefore, the Hierarchy has been embedded in the Government’s cycling policies for years.

Well, there really shouldn’t be a ‘dilemma’; the best solution for cycling on a given category of road should be quite obvious. In fact, there is only a ‘dilemma’ because the CTC are in the unfortunate position of having to accommodate the demands of the ‘no surrender’ group alongside the demands of those who might want to cycle in comfort with their children.

I also think it would be fair to say that in attempting to resolve this dilemma, the Hierarchy of Provision doesn’t really solve anything. As Freewheeler of Crap Waltham Forest put it –

The problem with the CTC’s Hierarchy of Provision is that instead of demanding concrete infrastructure which would make cycling safe, fast and convenient it dissolves into windy platitudes.

And that is exactly what we would get on Blackfriars Road; instead of clear demands for that ‘concrete infrastructure’ – cycle tracks which would make cycling a comfortable and pleasant experience for all – the Hierarchy instead provides a vague demand to ‘consider’ reductions in traffic volume and speed.

It’s nowhere near good enough, and thankfully, it seems to be on the way out, principally because it is fundamentally incompatible with the policy that Transport for London, housed in that building on this road, will be coming up with in response to the Mayor’s Vision. Transport for London will be segregating cyclists on the network, quite often in places where there is no reduction in traffic volume or speed, and they will be doing so as a first priority.

National policy needs to start catching up.

You are absolutely right. It starts with the word ‘traffic’, whereas the first word should be ‘livable’. Not the number of vehicle movements, but living should have priority, so transportation that gives the least amount of stress on a city needs to be supported first. So, 1. walking, 2. cycling, 3. Public Transport, 4. cars, 5. heavy goods transport.

I agree that the HoP is flawed, but what would you put in its place? If we were to start emulating the Dutch, as you believe we should, where would we begin, in 1973 or in 1992?

We should emulate the Dutch as they do things in 2013. No need to re-invent the wheel, they’ve done the real-world research into what works, and is truly safe, over the last few decades. The Dutch are re-building some of their early cycle tracks, re-laying them in ultra-smooth tarmac to replace brick paving, for example. They now know that cyclists prefer really smooth surfaces, and that this matters.

The first thing is to realise that there are different types of road, and different solutions for each. The HoP tries to apply to every road, from dual carriageway trunk roads to local housing estates, and that is one reason why it always fails. But the basic premise is of “sustainable safety” – roads and streets should be designed so that when people make mistakes the consequences are minimised. People in fast-moving motor vehicles should never be mixed with people on foot or people on bicycles.

The hierarchy makes no sense to me.

But it isn’t just that the order is somehow wrong. Or the confused/confusing use of the word “traffic”. I think it’s much worse than that.

Labelling the items from 1 (traffic volume reduction) to 6 (conversion of footways, etc…):

1 is a general statement of intent, but says nothing about how changes might be achieved in practice.

2 might simply refer to a drop in the actual speed limit applied, but this is not made explicitly clear. It might also mean other physical measures. Or some combination.

3 and 4 hint at more practical ideas but in the end they’re just vague terms – or as freewheeler says “windy platitudes”. Item 3 groups several differing terms together. For example, what do we mean by “traffic management”. A policeman standing directing cars perhaps? Surely the entire hierarchy is all about traffic management in some sense?

5 and 6 are actual suggested physical measures.

Of course I realise some related documents attempt to explain in more detail what these items might mean, but they’re so different from each other. Although they also overlap. For instance, it’s obvious that reallocation of carriageway space to cycle lanes/paths might be a way to reduce motor traffic volume (reverse induced demand, etc). So (4) is an example of a physical change you might make to try and achieve (1), which is more of a general aim.

How can we possibly try to compare these items, or sort them into any kind of order? To do so seems ridiculous to me. This clumsy attempt to (apparently) simplify the Dutch ideas has resulted in a short meaningless list.

So the hierarchy isn’t only flawed, it’s nonsense. And I’m just surprised so many people have placed so much stock in it for so long.

(sorry, got carried away again)

The hierarchy is rubbish, I think everyone can agree upon that. I am however starting to believe that there is a lot of value in a simple extremely high level “thing” that people can instantly grok. I’d think about some kind of matrix that matches street purpose against traffic volume, maybe something similar to my distilling of the CROW manual provision data http://media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m1epi8YjYz1qfzwpk.png

Yes. Weirdly enough there’s quite a similar table/matrix in Cycle Infrastructure Design itself, but once it has been presented it is basically ignored.

That’s a great distillation, much more useful than the silly HoP. Call it the Grid of Provision, or the Matrix of Provision perhaps!

I’d go slightly further than the graph suggests and suggest that a cycle track is desirable on the Urban Distributor roads with more than 2000 vehicles per hour, or thereabouts. Don’t give British highways departments a chance to do a cop-out!

You write: “Transport for London *will* be segregating cyclists on the network … and they will be doing so as a first priority.” Is this true?

According to the Vision for Cycling: “London will have a network of direct, high-capacity, joined-up cycle routes … There will be more Dutch-style, fully-segregated lanes and junctions; more mandatory cycle lanes, semi-segregated from general traffic; and a network of direct back-street Quietways, with segregation and junction improvements over the hard parts.”

TfL will offer two clear kinds of branded route, the strategy document says: high capacity Superhighways, mostly on main roads, for fast commuters, and slightly slower but still direct Quietways on pleasant, low-traffic side streets for those wanting a more relaxed journey.

Blackfriars Road is not currently part of the CS programme, and nor would it be appropriate to include it as part of the Quietways network, and so, unless the CS ‘network’ is to be greatly extended, roads such as this one are not likely to be treated for some time yet.

So what should be done in the meantime? Nothing? Nothing at all? Not even the bare minimum? The bottom line is that it would be either no trouble at all for the authorities to lay down markers on roads like Blackfriars Road, or a bundle of trouble. At the moment I get the feeling that, for them, it would be a bundle of trouble. The outcry from the pro-cycling lobby would be deafening.

“That’s rubbish!” they would say. “We thought the authorities had turned a corner, and now all they’ve done is to put some crappy markers on the road. That won’t encourage children to start cycling!”

People like me might try to make the point that these markers actually represent the thin end of the wedge, the foot in the door. People like me might say that following this course of action is the tried and tested approach, and is regarded by the Europeans as “a prudent course to follow.” People like me might make the point that for *existing* cyclists, these markers actually make cycling conditions both subjectively and objectively safer. Alas! it wouldn’t make a blind bit of difference. For the pro-cycling lobby, these arguments would be water off a duck’s back. Seemingly, doing nothing on roads like this one is actually a better option than doing something, because if the authorities only did ‘something’, this might set a bad precedent, or it would undermine ‘the campaign’ (because it would turn existing cyclists away from the whole idea of campaigning for separation from motor vehicles). And so the CTC’s ‘No Surrender’ cry from the 1930s resounds down through the ages: Either make the cycling provision excellent or don’t bother! – with the result that the development of the cycling environment proceeds at a most leisurely pace.

Demanding high-quality infrastructure first and foremost may well help to strengthen ‘the campaign’, but in practice it amounts only to “a strictly pragmatic and ad hoc approach.” However, ‘Cycling: the way ahead’ assures us that it is possible to “go much further” than this, and it begins with an acceptance that if it’s going to get better, it’s going to take *time*.

It took about twelve years for Cambridge Council to remove the car parking from Gilbert Road, this despite the fact that the scheme had widespread political support from the outset. Also, though the difference in build quality between the A24 in Morden and the A24 in Tooting is negligible, the difference in build costs is likely to be significant. Moreover, even if we still accept the view that interim schemes are a waste of *money*, it is important to stress that they are most definitely not a waste of *time* (in the sense that they can be installed quickly).

This is why I think Crossrider has it wrong when he says: “Interim schemes are a waste of money … Really TfL need to stop messing around with paint and only do Dutch things from now on, because that is the only approach that gives value for money.”

I am not so sure. What I do know is that London could have a functioning, comprehensive, city-wide cycle network by 2016, if only the pro-cycling lobby would allow interim measures on roads like Blackfriars Road. It is basically as simple as that.

What do you mean by ‘markers’?

Are you seriously suggesting that those painted cycle images on the road make the slightest bit of difference to anyone thinking of using a bike?

They’re crap, drivers don’t know what they mean, cars are often parked on the few that haven’t already been worn away by motor vehicle tyres. The “network” is useless if it isn’t useable. If it’s just signs and paint, it’s pointless.

We don’t need to design a new cycle network, because one already exists: all the main roads in London are the cycle network. They all need converting to being safe for anyone to ride a bike on.

A few pictograms of bikes won’t make a jot of difference to the speedway that is Blackfriars Road.

Am I seriously suggesting that those painted cycle images on the road would make the slightest bit of difference to anyone thinking of using a bike? Yes, actually I am. I have made the point, I don’t know how many times, quoting from Olaf Storbeck at Cycling Intelligence, that there is a group of cyclists known as The Enthused and the Confident (I include myself in this group, by the way). Anyway, according to research from America, this group makes up about 7% of the population. But where are they all? The research says: “They are comfortable sharing the roadway with automotive traffic…” So where are they?

Repeat markers and nothing else would be crap, I agree. But are they better than nothing? Really, come on. Wouldn’t they be better than nothing?

Drivers don’t know what they mean, you say. I don’t believe this to be true, but even if it is, so what?

If cars are parked on them, they’re in the wrong place. If they have been worn away, they would need to be replaced.

You say that the “network” is useless if it isn’t useable. I totally agree with this. And so, once the network has been planned, the first thing to do – the very first thing – is to make it useable.

If it’s just signs and paint, it’s pointless. No, SC, it’s not. If nothing else – if nothing else – it would make the network “useable”.

By the way, talking of pointless, what’s the point in waiting until 2020 for the cycling network to be “easily understood”? How is the network made “useable” if nobody can make sense of the signing strategy? Conversely, I have conceived a signing strategy which enables a network comprising of 70 or more routes to be coded using colours, and which can be understood by my eleven year-old niece. Why do you turn your nose up at this?

All the main roads are the cycle network. They just need converting to being safe for anyone to ride a bike on. Oh, right. Two things. One, how long do you think this would this take? And two, what should be done in the meantime? Nothing?

A few pictograms of bikes won’t make a jot of difference to the speedway that is Blackfriars Road. This may well be true, but why do you insist on taking a glass half-full attitude towards this? Why not try to see the positives from what I am saying? I am proposing the development of a comprehensive, city-wide cycle network, which is likely to be over 3000 km in length. A lot of this network is actually going to be quite good. Some of it won’t be (at least, not yet). Well, boo-hoo.

The thing I don’t understand – and I really do not understand this – is that the only publication out of Europe to answer the question, How to begin?, is so quickly dismissed by cycling advocates. I just don’t get it.

Whatever brilliant idea you have in mind for this junction or that roundabout can only be enhanced by being part of a greater whole. Surely you must see this.

David Hembrow has said: “I have argued for many years that there needs to be a more strategic view amongst cycling campaigners. That people need to be shown what is best so that a decision can be made with more information. Campaigners need to have vision. Fighting little battles over minor issues repeatedly does not make progress.”

The problem is, that it is not possible to take a truly strategic view simply by focussing on a network of Quietways and a dozen or so Superhighways.

Cycling: the way ahead says: “As soon as the network plan has been drawn up, some kind of checking mechanism is required to ensure that every time works are programmed they include the introduction of the amenities required for cyclists.” If you have your design standards in place, why would you oppose doing as much as possible at least bureaucracy first? I do not understand.

In terms of developing an amenable cycling environment, would you say that the best approach is (a) network first, and then a separation of functions, or (b) isolated bits of quality infrastructure first, and then join up the pieces? Answer the question, why don’t you?

You’re quoting from an article called “What the Yanks can teach us”? Are you talking about that country with an even lower cycling modal share than the UK? The one that is only just discovering “bike boxes” and “sharrows”? Tell you what, let’s forget the USA when it comes to cycling, there’s somewhere much better, and it’s easier to get there too. (Although they have the strangest accent.)

So where is this 7% of “Enthused and Confident” riders? I don’t know. Perhaps the 7% figure is wrong – perhaps it’s nearer 2%. Makes sense, all of a sudden! Lambeth council has been laying down these markers like mad in the last few years, but I still wouldn’t fancy my chances circling the Imax on an omafiets.

There’s no need for a new mapping system, all the routes already exist. To get from Waterloo to Euston, the obvious route is over Waterloo Bridge and up Kingsway to the top, crossing over Euston Road and you’re there. If that’s not the route – if bike users are instead directed along a complex network of back streets – then we’re not going to convert many people off the buses and tubes. Those “Enthused and Confident” cyclists will know the way already, and go straight up Kingsway, as I described.

Do you really think that there are legions of people just waiting until there’s a new map out, or some pictograms painted on the road, before taking up cycling? I don’t understand where you’re coming from. Here’s a major UK local highways authority, for the first time ever, saying that they will install segregated bike paths, and your answer is “hang on chaps, it’s better to have some pictures of bikes painted on the road for a few years first!”

The paint-on-the-roads stage has gone. We’re beyond it now. It’s time for concrete and tarmac.

I agree with you, we should have the network first – but that stage is already done, we do have the network. Open Google Maps and you can see it: all those green, orange and yellow lines are the main network. The white ones are the smaller streets. It exists already, no need to start drawing up new maps. We just need to change the roads so that anyone can ride a bike along them.

Of course I’d like to cover the whole country in infrastructure overnight! But that’s not feasible, is it? So the answer is: isolated bits of infrastructure where they’re most needed (junctions, fast/busy roads) then join up the gaps, in order of neediness. Does that answer your question?

Just because things have taken a long time to improve in the UK before doesn’t mean they can’t improve much quicker in future. Just because we might not get a really nice complete Dutch-style network in London tomorrow doesn’t mean we shouldn’t ask for one.

A very important consideration, as important as the decent infrastructure being built, is the implicit message sent by the authorities starting to spend reasonable sums of money on cycling at last: cycling is now a proper mode of transport! People will naturally value transport modes according to how they see transport planners valuing them, and thus investing in them. A shiny new station with modern trains encourages more people to use the train than old un-maintained railways. In the same way I think nice new expensive-looking (and motor-traffic free, of course!) cycle tracks will get people cycling more. Crap pavement conversions and cheap painted cycle lanes just reinforce the message that cycling is not highly valued.

As soon as highway authorities treat cycling as a first-class mode of transport, they’ll realise that investing 10%, 20% or even 30% of their budget on decent Dutch-style cycle tracks is actually not only a Good Idea but is also an extremely good investment to make. We just need to jolt them out of the old-fashioned thinking that cycling is just for children, and that cycle provision should always be done cheaply, and things will change very quickly.

This is changing the subject slightly, but, ultimately, another thing that will need to change, if the Mayor and TfL succeed in this infrastructure-based cycling revolution that they have proclaimed, is the nature of cycle training. As more and more segregated (or “separated” as some people like to say) infrastructure comes on-stream, training will have to change to accommodate this, becoming less concerned with teaching assertion and the taking of the lane on shared busy roads, and more concerned with how to use the dedicated infrastructure, knowing the rules of it and the rules of the road, how to interact with pedestrians and how to interact with large numbers of other cyclists on the same infrastructure. It will have to evolve, in short, to closer to what it is in the Netherlands. And this process will itself make cycling more inclusive, by removing much of the implication about needing to be fast, fit and steely-nerved to cycle on the roads, and I would expect the graduates of such training to become far more likely than they are at present to turn into long-term cyclists.

Nice cafe on Blackfriars Road! The street is massively wide and is a corridor for people travelling to the area as well as having an extensive residential area. A protected cycle track would be a doddle.

I have a theory that (in the past at least) transport planners would only put cycle lanes on roads which weren’t wide enough to do them properly – hence narrow, stop-start lanes clashing with bus stops, odd bits of parking, side turnings and pretty much everything else. Blackfriars Road is a great example of a road where it seems a bit ridiculous that nothing meaningful has been done to date (it does have a narrow cycle lane in parts of the gutter). Why on a road this big we’re still at the point of not even having a painted cycle lane meeting basic standards says a lot about the real commitment to cycling to date. The potential for improvement is massive, but nice words aren’t going to make it happen, so I will believe it when I see it.

Reblogged this on Simply Green Buildings and commented:

Lets hope the heirarchy of provision is dropped ASAP – this could be what has been holding back proper provision for cycling for years…

I did a campaigning workshop in Norwich a few weeks back and we were talking about our ‘elevator pitch’ – the 1 minute getting across of ideas to whoever it would be (if it was Cameron, I’d probably just hit him with a bike pump but there you go). Anyway, mine started with (I am in Ely Cycle Campaign btw) that I was interested in increasing cycling provision not for the 1% in Ely who cycle now but the 20-50% who would if it were safe enough. The feedback was this was a really good way of getting across the scale of the issue. This idea of a hierarchy of provision works on the same basis, work with the majority first, it seems beyond TfL’s comprehension that they could actually be serving more people if they took private vehicles out of the picture.

Holland have recently completed a 5 lane extension to the A2 between Utrecht and Amsterdam according to my Mum who lives over there and my understanding is that driving in Holland is less stressful and not less convenient than here, it’s just properly organised. They think about where and how people use cars as much as they do bikes and invest in both. Where there is the need for car parking (out of town furniture districts come to mind), it is plentiful. When you want to go and mooch round the shops and have lunch, you get a very cheap park and ride and free public transport for 5 people for the day. If you work in the city, you have public transport to get you there or you can easily cycle. If you work on an industrial estate in the middle of nowhere (and there are plenty of them in NL) there is plenty of parking but they are also serviced by bus routes and cycle routes – I used to cycle 45 min to one on the outskirts of Utrecht along the A2 and I lost 2 stone within 2 months of starting work there. I’ve been back in England for 13 years now and I’ve put on about 4 stone and I can’t get on a bike anywhere near as much as I’d like. And I don’t have a driving licence.

Anyway, my point is i don’t know how to get through to 50 year old men in councils (like Ely or London) who just can’t see how their comfortable car is such a problem, however we seem to put it, they are in the way of making the quality of life in the UK any better.