When I arrived in St Albans on a Saturday morning earlier this month, I encountered a long, completely static queue of motor vehicles. It turned out they were all waiting to enter the Christopher Place car park in the city centre, which has 180 spaces, but was already full.

The queue snaked around the corner, winding for several hundred metres around the city centre streets.

The queue snaked around the corner, winding for several hundred metres around the city centre streets.

As far as I could tell, this was completely normal for the drivers and passengers inside – nobody was getting angry, they were just patiently waiting for other people to leave the car park so they could move up one slot in the queue. The sort of thing that probably happens every Saturday. And of course they are paying for the privilege.

As far as I could tell, this was completely normal for the drivers and passengers inside – nobody was getting angry, they were just patiently waiting for other people to leave the car park so they could move up one slot in the queue. The sort of thing that probably happens every Saturday. And of course they are paying for the privilege.

I rarely drive, but when I do what immediately hits me is the frustration of being ‘caught’ in this kind of situation – having to queue, having to wait, often so far back in the queue you have no idea what’s causing the hold up, and with no way of finding out. Driving in urban areas is frequently a dispiriting, painful experience, made so because everyone else is doing it.

Unfortunately, as far as I can tell, these kinds of problems are going to get worse. More and more of us are going to be living in towns and cities, a function of increasing population, and a continuing trend away from rural dwelling to urban dwelling. 53 million of us already live in urban areas. That is going to increase pressure on the existing road network, if we continue to travel around as we do now.

There are two long-term solutions to this pressure – the first is to ‘spread out’, to redesign our towns and cities to accommodate even more motoring. What could be called the ‘Milton Keynes’ solution, or perhaps the Lord Wolfson ‘flyover’ solution.

What designing a town for mass motoring looks like – Crawley town centre

If you don’t like the look of that, the only other solution is to change the way we move about in urban areas, to reduce pressure, by maximising the efficient use of road space. That means prioritising walking, cycling and public transport, policy that will require sustained investment in redesigning the way our existing roads are laid out, to make them safe and attractive enough for people to switch away from car travel for short urban trips.

Road space reorganised. This streets carries around 60,000 people a day, cycling and on public transport.

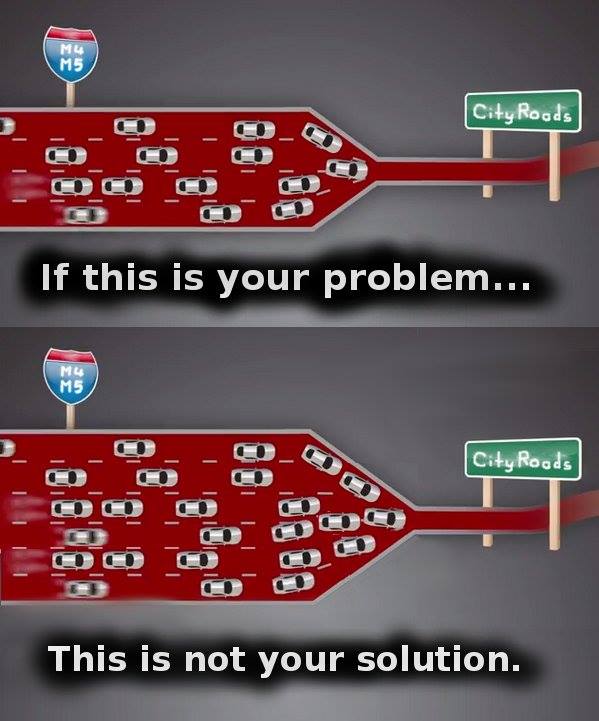

The reason I say our problems are going to get worse is that we aren’t prioritising these kinds of sensible solutions. The vast majority of the ‘investment’ announced by government continues to be spent on major road schemes that will worsen congestion in urban areas, by pumping more and more motor vehicles into them, instead of focusing that investment on solutions within them. Towns and cities will not cope, and congestion will be worsened, as a direct consequence of these policies.

Amazingly these kinds of announcements are presented as ‘benefiting’ ‘towns and cities across the country’, when quite the opposite is true. Building a massive road scheme between Oxford and Cambridge is not going to be helpful for congestion in either city, because it really isn’t very easy to drive around within these cities already – funnelling more cars into them is completely counterproductive.

In a nutshell. From here.

Energy and investment should instead be focused on enabling space-efficient alternatives within both of these cities, and on prioritising rail links between them, which can deliver large numbers of people right into the city centres in an efficient way. And these solutions are far more cost-effective than massive road building schemes.

We seem locked into repeating the mistakes of the past fifty years, assuming that people want to drive in vast numbers because so many of them are doing so already, when in fact these individual decisions are largely a function of the poor quality of the alternatives, and of the way that motoring has been prioritised by the way we have designed, built (and rebuilt) road space in urban areas. But worse than that, there is a curious failure to recognise that these ‘solutions’ will no longer work, not without urban rebuilding on a massive scale.

The people queueing to enter that car park in St Albans certainly do not need major road schemes pumping more cars into their city centre. They need sane alternatives within the towns they are travelling, alternatives that will allow them to make the same short trips they are making, but in a way that is more efficient, and that actually frees up road space for the people who will still need (or want) to drive.

A typical Dutch town – the kind of mobility we should be enabling

We need the kind of engagement on the actual issues shown by Northern Ireland’s Infrastructure Minister, Chris Hazzard –

When looking at the economy… we continue to talk in the House and on the public airwaves about moving cars. We need to talk about moving people. Moving people in and out of Belfast city is good for business; moving cars is not.

What are we to do after York Street? Are we to bulldoze half of Great Victoria Street because we need two extra lanes in Great Victoria Street? Are we to demolish Belfast City Hall because we need a bigger roundabout at Belfast City Hall? We need to talk about moving people, not cars, in and out of Belfast.”

Exactly right – we aren’t going to solve our problems any other way.

It’s why the Dutch build railways, quite nice railways I might add, usually between 130 and 160 km/h on double tracked, electrified, accessible stations with easy ticketing systems and bicycle rentals with the same ease as the boris bikes are in London, between geemente centrumen and their motorways or 100 km/h autowegen as either ring roads, bypasses or links between the cities usually over 50 thousand people. the countryside roads don’t have much traffic anyway so only small roads are needed to service them. And through roads aren’t slowed by side accesses or the like directly off them, and they are well managed during times when traffic is slow or crashes happen, keeps people quite safe.

Traffic demand is inelastic, the billions of people around the world need to get there somehow, as does the goods of the world. But the mode of transport doesn’t have to be with cars. Traffic demand in cars will switch if there are suitable alternates, like better and more efficient railways, especially for freight movement, underrated in Europe, or cycleways for passenger transport in a city and sometimes even between cities.

The Oxford to Cambridge link road isn’t intended to reduce congestion in those cities. It’s purpose is to run in parallel with the ‘new’ railway, connecting the two places to form one side of the high-tech, high-finance, high-politics triangle that is going to save Britain’s economy. In practice, GRIP and funding priorities mean it’s likely to be finished before the railway, despite that having been on the cards for a few years.

I expect the DfT will leave it to the individual LAs to deal with traffic on its way to the science parks.

“The Oxford to Cambridge link road isn’t intended to reduce congestion in those cities.” But the unintended consequence could well be to increase congestion. A bit of joined up thinking would not go amiss. They might even encourage it at the two universities.

Not even so unintended, more like indirectly intended, seeing as the point is to move people (in cars and buses) and goods from one city to the other (and from both to London).

“The people queueing to enter that car park in St Albans certainly do not need major road schemes pumping more cars into their city centre. They need sane alternatives within the towns they are travelling, alternatives that will allow them to make the same short trips they are making,”

nah, they’ll just scream for more car-parking spaces…

Pingback: Right and wrong solutions to urban congestion

What do you say to people who tell you that actually the problem is:-

+ Speed limits too low in the city

+ Too many cyclists blocking up traffic

+ Too much road space taken away for cycle lanes

+ Too many busses in the way

I’ve seen all of those used commonly. Some of them by supposedly sane authorities on road use (actually the AAs spokesman). They seem impossible to convince otherwise and those people who are wedded to their cars (which seems to be the majority) and have already decided on the answer they want (more roads! more speed! less restrictions!) are nodding agreement.

Hello Mark

Another very interesting blog post! I have noticed that you don’t talk about CO2 and climate change in your blog. I could think of a few possible reasons for this:

1. There are lots of benefits to increased cycling that have nothing to do with climate change.

2. You want to get away from the idea that cycling is something which you ought to do, but is not particularly pleasant, like eating kale!

3. It might lead to lots of fruitless argument over whether climate change is real.

4. It’s just not your area of interest.

Is it some combination of these, or something else which I have not thought of?

I mention it here because in this blog post you talk a bit about longer distance transport, such as rail. In the second edition of Zero Carbon Britain 2030, by the Centre for Alternative Technology, there is a chart showing that 19% of emissions from cars are from journeys of 5 miles or less. This is less than I might have thought. I’m not sure how they calculated this, and whether they assumed fuel economy is the same on trips of different lengths. (There is a reference to DfT data, but I haven’t worked out how they calculated it from that). This made me wonder whether cycling might make a bigger contribution to reducing emissions by enabling more long journeys to be made by train, rather than by replacing the car for short trips, although clearly this is still a valuable contribution. Perhaps reductions in congestion are also a significant part of the reductions in emissions from increased cycling. It would be good to know the assumptions behind the CAT chart, or if there is a better one.

Good point, though I’m betting you’ve already answered your own question with those four points.

I’d add a fifth – which is that car use in the UK is only a tiny contribution to global CO2 emissions, and asking motorists here to stop using their cars for that reason is asking them to make a sacrifice that isn’t going to make any noticeable difference unless everyone else does their bit at the same time. So, purely in my opinion, it would only make sense in the context of arguing about the issue at a bigger, global, level.

I know some people are very keen on ‘act local’, but I just find it hard to share that emphasis. Local, individual, lifestyle changes don’t have enough effect to motivate most people to engage in them.

The arguments about local (non-CO2) pollution and physical inactivity and just plain convenience for all, to me seem much more compelling when engaging in political arguments that are unavoidably local.

Yeah, the difference between the CO2 issue and the other issues, is that for the latter the positive results can be experienced immediately and directly by those who will be involved in the changed behaviour. Which also means it could benefit from a kind of trickle-down or ‘power of a good example’ (i.e. maybe there’s a chance that if London greatly improves its situation other parts of the UK might decide its a good idea to copy it)

Whereas with climate change the problem is unavoidably a global one so you have much more of a ‘tragedy of the commons’ situation.

Hello Michael

Good point also!

I think it depends what the target audience is. I agree that the non-CO2 benefits of increased cycling are more immediate and tangible, meaning that they appeal to a wider audience. Who is the target audience for this blog?

I see what you mean about local arguments. But are the political arguments purely local? It’s my understanding that some of the main reasons why cycle infrastructure is mostly pretty dire in this country is a lack of funding and national standards. These are national issues.

As I’m sure you know, the UK has a target of reducing emissions by 80% by 2050, relative to 1990 levels. Ideally, nationally policies that aim to get us towards this target would weigh up all the different options. CO2 savings from more cycling *ought* to be of interest to national policymaker people (but I think this is a small percentage of people!).

I think I know what you mean about “act local”. I think that if significant progress is to be made in reducing emissions, little of it is going to be from telling people “be good” without changing their environment. What is needed is significant changes in the environment/system in which people live. My area of interest is in energy and buildings, and in this area there is the idea that we just need to tell people to turn the heating down and put on a jumper (which I think is likely to have little effect). I think there are some parallels to the idea that we just need to tell drivers and cyclists to “be nice”, without making significant changes to the street environment.

Sorry this is a bit of a ramble…

My take, though, is that as far as climate-change is concerned, the national level is still ‘local’.

To make significant changes to the environment requires political will, and I’m dubious that much such will (which ultimately has to be bottom-up, I don’t think ‘national policymakers’ have much autonomy on the question) can be generated with reference to climate change – because that is such a global-level issue.

Besides, I think more in terms of single cities. You aren’t going to persuade Londoners to change their streets for the good of the planet, but you might be able to get them to try it for the good of Londoners. And if it is seen to work, it can probably inspire other parts of the country to do the same.

Come to think of it, one reason why I feel so strongly about active-travel is it seems like a rare issue where positive results could be achieved rapidly enough to persuade large numbers of ordinary people to press on with it. Unlike other political issues, about which I feel deep pessimism, including climate-change-prevention.

But, thank God, the two issues are not in conflict – what’s good for obesity, accident-rates, and local air-pollution, is also good for CO2 reduction. Issues don’t always work out that way, so that’s something to be thankful for.

All of those cars queuing on the carriageway are obstructing the flow of traffic, including through flows NOT wanting to get to a parking space. It is about time that cities and towns got a frip of the position and take an example from Nottingham, which has for at least 20 years enforced the ‘moving on’ of any vehicles which block a traffic lane by queuing for a car park space on the carriageway.

Carriageways are provided by the roads authority for just ONE purpose, the passing and repassing of traffic, and obstruction (Highways Act 1980 s.137) carries a fine of up to £1000 – but (in London at least, if not elsewhere) can be enforced by the issue of a Fixed Penalty Notice by a Council Enforcement Officer, if their system is set up appropriately, much in the same way that as well as cyclists driving their carriages on a footway across Tower Bridge the TfL Roads & Transport Officers can also fine drivers for the same offence (Highways Act 1835 s.72) if they catch them driving a car on the footway.

I feel a Mayoral Question coming on.. given that TfL Enforcement Officers have been issuing FPN’s for cyclists for breach of s.72 HA 1835 when riding on the footway of Tower Bridge, and the Mayor provide details of the number of FPN for Section 72 offences, and a break-down of the numbers issued to private car drivers, taxis and passenger vehicles, freight vehicles (if possible split by weight at 7.5T GVW) and cyclists.

Isn’t it wonderful that people are willing to spend money on a vehicle that limits their freedom to move around in urban areas, while the ads that sell them never show the harsh reality of driving? A little while ago my neighbours drove off with their car and about 30 minutes later I took my bike and rode to the centre of the city, where my neighbours were waiting to park their car, just like in the article. The weather was fine, they could have walked or, god forbid, taken a bike. One of them is from the US, maybe that’s the reason.

Your point about the ads is very relevant to lots of motorist/cycling issues. They often go further, showing heavy traffic and then depict the magical car they are trying to sell taking a hard left turn out of traffic (did they check their mirror before doing this I wonder) and then zooming up and down side streets with exhilarating freedom.

This utter disconnect between the advertising and the reality of driving is a big part of the reason that so many motorists are frustrated to the point where they think it is ok to deliberately endanger other people. They paid a lot of money for their car but they aren’t zipping around in a thrilling manner with an attractive model in the seat next to them. That must be someones fault. Luckily the motoring media is able to supply the answer: it’s cyclists’ fault. It is their fault that you are stuck in a line of traffic going nowhere because somewhere down the road people are queuing to get in to a car park.

It would be quite interesting if you asked your car driving friend how long it took them

Most people seem to only include the time actually driving, so time to queue and time to walk from car parks is often simply neglected.

On top of that I notice that many people have a journey time in their head for journeys such as commutes that they do regularly. If they are held up they are “delayed” and the delay is never added to the journey time, so you hear people state that it takes them 40 mins to drive to work but they have been delayed 4 times this week!

A good example of the tragedy of the commons.

Give everyone a car, and no alternative but to use it…

All those cars also need to be parked at home of course. And where better than all that wasted green space aka your front garden? Research commissioned by the RHS in 2005 and 2015 has revealed that around three times as many UK front gardens are now completely paved over compared to 10 years ago – a total increase of 15 square miles of ‘grey’. This means that more than half of the total surface area of UK front gardens is hard surfacing.

The permitted development planning laws are far too lenient and most LAs don’t enforce the weak requirements to seek planning permission. Gardens play a crucial role in urban areas, helping to protect against flooding and extremes of temperature, as well as supporting wildlife and providing health benefits. For more info: http://www.rhs.org.uk/urbangreening

So allow for a frontage of say 6 metres per house which is say 3 metres deep all paved and thus having no attenuation effect on rainfall – what lands on the paved surface goes straight into the drainage system. Rounding up (to allow for the paved area down the side of the house or similar) that’s 20 sq.m for every paved over garden, and say a belter of 2″ (50mm) of rain lands in a storm and 1000 litres per front garden goes straight into the local watercourses.

Car parks also create the problem – we had a good example when all 13000 car park spaces at Bluewater were vacated at closing time in January 2016. Based on an optimistic 6 seconds per car to clear an exit ‘gate’ and move freely away on a road – with a single ‘gate’ it would take around 32 hours to get the last car out. However with a nominal 2 gates heading to each of the 4 points of the compass the figure eases back to around 4 hours, which allowing also for a small spread of departure times delivers the reported 3 hours queuing to get clear and away on the connected roads.

I see this daily in Glasgow, where the roads connecting to the M8 seize up from around 16.30 on a weekday (earlier on Fridays) and yet by 18.30-19.00 I can look along one of the main queuing routes (Sauchiehall St and not see a single vehicle travelling along it for almost 1 Km) outside the surge to get in to car parks in the morning and the surge to get out in the evening the streets are very quiet.