An exercise I’ve been planning for a while is to categorise all the streets and roads of the town of Horsham. Some of this work had been started by Paul James of Pedestrianise London. A while back we had discussed a Sustainable Safety categorisation of the town, deciding which streets and roads should fall into which category of through, distributor, or access road, and Paul had started a base map of distributor roads.

With some free time over the weekend, I’ve managed to bite into this exercise even more, starting at the opposite end of the scale, and I’ll discuss my method and the outcomes here. I think it’s a useful thing to do for towns and cities in Britain, for a number of reasons. Firstly, it gets us thinking about which roads and streets require more expensive interventions like cycleways; which streets might require some kind of filtering; and which streets (actually the vast majority, in the case of Horsham) that don’t require any action at all. Secondly, it also helps to identify the ‘problem’ areas, those roads and streets that don’t fall immediately into an obvious distributor road category, but that will require some action.

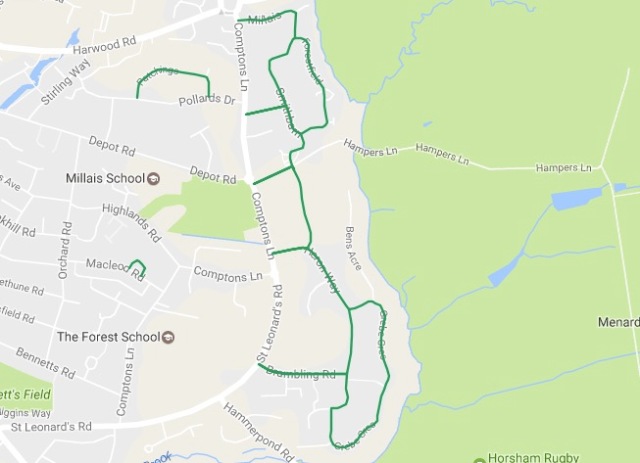

The first step was to plot all the cul-de-sacs in the town. By my definiton ‘cul-de-sac’ I included every single road or street that has a single entry and exit point for motor traffic, regardless of length – in other words, every driver using one of these streets will have to leave via the point they entered.

This includes the obvious short cul-de-sacs –

… as well as some much longer sections of road.

I think it’s a reasonable assumption that all these cul-de-sacs are by definition ‘cycle friendly’, without any adaptation, or addition of cycling infrastructure. Even the largest – like the one above – will only include a hundred or so dwellings, meaning that traffic levels will still be reasonably low. The key point is that cul-de-sacs will have no ‘extraneous’ traffic, i.e. drivers going somewhere else. The only drivers on them will be using them to access dwellings or properties within the cul-de-sac itself, meaning even the largest ones will not have a great deal of motor traffic.

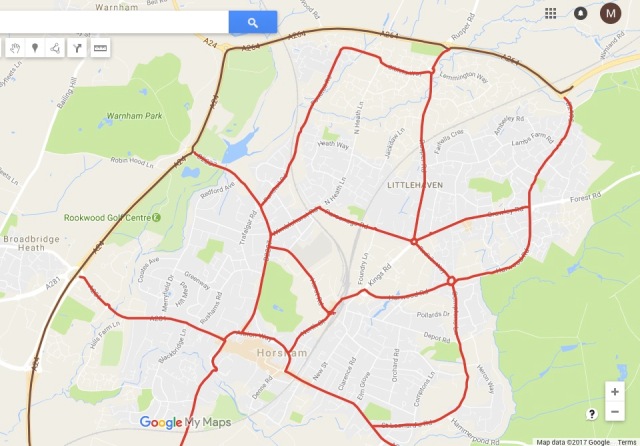

Once I’d finished plotting all of these streets, I could then take a look at the town overall. To my slight surprise, a very large percentage of the town is composed of cul-de-sacs.

All the streets in green are essentially safe enough for anyone to cycle on – they will be quiet, low traffic streets, requiring little or no modification.

The map also shows a clear distinction between housing age. Houses built in the period before mass motoring tend to be on ‘open’ streets, like this late Victoria housing area to the east of the town centre.

This contrasts strongly with the areas of post-war housing – particularly that built from the 1960s and 1970s onwards – in the northern parts of the town, where nearly every single residential street is a cul-de-sac.

This is perhaps a consequence of the influence of Traffic in Towns, but it’s most likely a rational response to the increasingly pervasive influence of the motor car on society. In the Victorian era, there wasn’t any need to build ‘closed’ roads, because there wasn’t really a ‘traffic problem’. The cul-de-sac emerged as a design solution to that problem, allowing people to live on streets that were safe and quiet, not dominated by people driving somewhere else. The challenge, of course, is ‘converting’ the streets of the pre-motor car age into ‘virtual’ cul-de-sacs, creating those pleasant and safe residential environments that the majority of the town already enjoys, and this exercise reveals which particular streets will be an issue – something we will come to.

I then chose to ‘add on’ to this cul-de-sac layer those residential streets that have more than one entry and exit point, but will realistically still only be used for access. For instance, this network of residential streets to the east of the town.

Clearly, it’s possible to drive through and around these streets, but there’s no real reason to do this unless you are accessing properties on them – so they fall neatly into another category of streets that require little or no remedial action to make them ‘cycle friendly’. Some of this requires a degree of local judgement, and knowledge about the routes drivers might be taking as short cuts, but I’ve been quite conservative in the ‘open’ streets I added to this category.

Add these two layers together, and we can see that even more of the town becomes ‘green’.

I then wiped the slate clean, removing both these layers, and approached the town from the opposite end of the scale, adding the obvious through road (the town’s bypass), and what I consider to be the distributor roads – the roads that will remain ‘open’ to drivers, and that will therefore require cycling infrastructure to separate people cycling from these higher volumes of motor traffic.

There might be a case for adding more roads to this category, or removing some from it – again, this is a matter for local judgement, and there is one road on this map that probably shouldn’t be in this category. (I’ll leave you to spot it!)

We can then add all the layers together to reveal the streets and the roads that haven’t fallen into any of these categories.

The good news is that there aren’t very many of them. Given the discussion above, they mostly lie, as expected, in the areas of the town built before the middle of the twentieth century – the 1930s housing to the west, and housing of similar age (or earlier) to the east).

Early 20th century housing to the west of the town centre. A fair number of ‘unclassified’ streets that will require some kind of action.

What kind of intervention is required is obviously a matter for local discussion – there might be an obvious (but naturally controversial) filter that could be applied in many of these locations, but on slightly wider streets painted lanes might suffice, given that motor traffic levels are not exceptionally high on any of these streets. Or there might be no need for action at all.

The final step – and one I haven’t started on yet! – is to add on the existing walking and cycling connections between these areas, and to highlight obvious connections for cycling that are not legal or need to be upgraded, or that simply don’t exist at present. One particular problem that has emerged from this exercise is railway line severance in the north east of the town – it would be good (albeit expensive) to get a walking and cycling underpass, under the railway line, connecting these large, otherwise isolated, residential areas.

Clearly, doing this kind of Google Map is only a first step. It’s easy enough to draw lines on a map; the harder part is actually getting the interventions in place. But it’s very helpful in focusing attention on precisely where those interventions are required. The main roads jump out; but also the more problematic roads in-between the obvious main roads and the quiet access streets, that remain white on my map, and will need some discussion at a local level.

Let me guess which road should not be a distributor by your standards, er, Albion Way between North St and the B2237?

Can I play ? The road that probably shouldn’t be a through road – is it Pondtail rd. ?

I suggest a lot more work is needed 🙂

What is the age of an area?

It’s road width? How are cars stored? What are the radii of curves? What are traffic speeds?

What are the key desire lines?

What are the population demographics? % car ownership?

Is there any UK urban area where cars are not stored all over the roads ? Number of cars expands until there is near logjam.

I am only envious of the number of cul-de-sacs . Round here most roads are pre 1920 so rat-running is endemic limited only by railway lines (plenty of those) and rivers.

I’ve been thinking about the “low traffic” streets in Oxford, and I’m not so convinced they need _no_ work. In some cases there are longish segments of cul-de-sac which still carry moderate amounts of traffic and which, while notionally 20mph, are laid out to make 30+mph a more natural speed. Also, poor visibility at junctions can be a problem, along with potholes and street furniture. But any improvements here should, I’m adamant, not be argued for as cycling improvements, but as “livability” improvements more generally. It should be safe to cycle on these streets, but also to play around or even on them. People in wheelchairs or pushing prams should be able to get around comfortably and safely.

* 15mph speed limits, possibly modifications to make <20mph seem natural

* junctions with raised tables, level pedestrian crossings, and corners engineered to severely discourage parking (to protect sight lines).

* surfacing to cycling standard

I don’t think it’s an absolutely hard and fast rule, to be honest, just a reasonable starting assumption. I’d be interested to see your Oxford examples – certainly the worst example in Horsham (the long cul de sac featured in one the images) is fine, although it is definitely low density housing. There may be some changes required depending on the type of activity on the cul de sac, too, of course – an industrial unit with lots of HGV movements would require separation.

This post is now on my bookmark bar. Thank you for writing

this.

Fascinating. And something that could be automated reasonably easily, I think, using OpenStreetMap data: feed in any British town, get a map of what a Dutch network might be out the end of it, plus a list of the “obvious connections” to be tackled as a first stage.

I can’t pretend I’m not tempted. And maybe this would be a good target for that DfT innovation money towards doubling cycling that has just popped up…

An issue that you haven’t discussed is parking. In some places an estate will be full of non-residents’ parked cars during the day, with a morning and evening rush hour at just the time when children might otherwise cycle to school. The answer might be residents-only parking, but that may not be popular with the residents who will need permits, let alone the displaced drivers. And even in a short cul-de-sac with less vehicle movement, parking on both sides leaves a narrow traffic lane that would be intimidating for some people. It also makes turning difficult, and reversing is a risky procedure if there are pedestrians and bikes around.

We do have a controlled parking zone which has been in place for over a decade, which does help, although interestingly it only covers the ‘older’ (and more open) types of street distinguished in this post.

In some of these Victorian streets cars park half on and half off the pavement on both sides of the road leaving just a single lane along the road. Official parking bays are squeezed in even next to junctions and where they obstruct the free movement of traffic.

Although there is competition in some locations from commuters, shoppers or the school run, this is largely being managed by CPZs. the main issue is high car ownership -many households have 2 or 3 cars even if they have no driveway.

Once ‘overparking’ has been established on a street, it cannot be reversed because there would be outrage from residents left unable to park the cars they already own. In addition, the council explicitly favours staggered parking as a cheap means of traffic calming. Yes, parked cars are effective at slowing the traffic and even reducing rat running, but they have toxic effects too:

It is difficult, unpleasant and sometimes too crowded using the pavements.

It is especially bad for those with wheelchairs, buggies or small children on foot, scooting or learning to cycle

Visibility is very bad, especially for children crossing the road

Cycling on the road is tricky, especially for children and novices: you need to weave around parked cars, watch out for doors opening and negotiate with oncoming drivers some of whom think that cyclists should always give way to cars

The dominant visual feature of the neighbourhood is cars

Did something similar, but looking at connectivity in all North Northants towns, colouring up cul-de-sacs purple, links blue, streets that connected at both ends to something else- red, based on work by Karl Kropf on urban morphology. Big issue with cul-de-sacs is that even though they might not need loads of work to make them more cycle friendly, they don’t tend to take you anywhere and don’t add up to a useful network. Having said that, we came to the conclusion that the place to spend the money was the streets which integrate best with every other street in the network, using the software tool Space Syntax (now available free open source). This was, consistently, the historic radial streets which are already busy with bus and foot traffic, so are not cheap or easy to resolve, but where it would be worth investing and not bother investing in all the more peripheral routes which although they could be made better, didn’t offer as much connectivity. You can see the original study here: http://www.nnjpu.org.uk/publications/default.asp

Cul-de-sac layouts can be very functional for non motorised transport if the permeability is there, such layouts including extensive pedestrian or cyclist connectivity are used in other parts of the world. But they need to be designed in from the start of a town rather than added later (http://cyclingchristchurch.co.nz/2017/01/02/what-price-for-a-cycleway/) and as I recall there is a general objection to permeability in the UK based on wanting to eliminate movement to control crime (http://www.lincolnshirelive.co.uk/hundreds-of-new-homes-planned-for-lincoln-city-centre/story-29585980-detail/story.html) that comes up repeatedly.

Pingback: Plotting a Dutch network onto a British town (As Easy As Riding A Bike

You could just cycle on whatever roads you want to cycle on. Simples. No expenditure of public money required!

Yes, you could do that. If you want to see how successful that policy is in encouraging increased active travel, just take a look at the modal share statistics for transport in the UK. I’ll give you a clue: pretty unsuccessful.

Similarly, if you want to get a feel for the costs of such a policy, just google “Obesity Statistics UK”.

This last part may require some critical thinking, but now you need to decide which provides better value for the public’s money: investing in active travel, or providing treatment to people with illnesses related to inactivity?

Ijon needs to Google “How do people respond when they feel like they are being bossed around?”

“IF you want X, just do Y” is ‘bossing people around’?

I prefer to lead by example, and by calmly helping people come to the conclusion for themselves that cycling on the public highway is not dangerous or difficult.

I do NOT advocate spending huge amounts of other people’s money on stupid projects which cause more problems for the cyclists than they solve. And when you spend other people’s money on badly designed infrastructure from which BY FAR the majority will never benefit, especially when the work is accompanied by patronising statements, then all you achieve is to wind everyone up and harm the case for good stuff.

We already spend huge amounts of other people’s money on stupid projects which cause more problems for everyone than they solve. See a large proportion of major road-building projects (where the sums involved absolutely dwarf the small amounts spent on cycle infrastructure).

PS why should I care about ‘cyclists’ as such? That’s a tiny group, a significant number of whom have misguided ideas (like imagining they are a special shining light that everyone will follow onto the roads like the Pied Piper). I care about myself and the wider population, not ‘cyclists’.

This might surprise you, pm, but I couldn’t agree more. You see, the root problem here is Other People, spending Other People’s money on what Other People tell them are Other People’s problems. This. Is. Why. State. Should. Be. As. Small. As. Possible. Otherwise, the Civil Servants just get splashy with the cashy (refer Magic Money Tree) and too big for their boots. Plus, it creates an environment ripe for corruption.

The terrible Cycle Super Highway in Leeds and Bradford was built predominantly with an EU grant. I can’t think of a better example of the above.

Like you, I also try to avoid classifying my fellow humans in arbitrary ways. I drive, fly, cycle, walk – who cares what method I choose when? I try simply to choose the most appropriate method for the journey.

Roads and motor vehicles are great – the problem lies with PEOPLE choosing to use their cars at the wrong times, in the wrong places, for the wrong reasons, and in the wrong manner.

To solve this problem, we need to address people’s perceptions and prejudices – training. In the meantime, let them sit in their nice warm cars going nowhere fast. Who am I to be so arrogant as to try and convince them that cycling is great? They must come to this conclusion for themselves.

I once tried telling people that the millennium did not end at midnight on 31st December 1999… but then I realised that if they wanted to believe it did, then who the hell am I to tell them otherwise?!

I think this comes down to the same disagreement I always have with some people, in many different topics. A lot of people have a peculiar, near-religious, faith in ‘education’ and ‘training’ as a solution to all ills, from racism to declining social-mobilty. Despite the lack of evidence that it actually works.

Anyway, it sounds like you are one of them libertarians (libertarianism – the quickest route to authoritarianism yet invented, see post-Soviet Russia). If so you ought to be mostly aiming your ire at the massive subsidies we have for car-users, from free-parking, to uncosted pollution, to subsidised health-care required due to physical inactivity and that pollution’s effect on everyone, through to failing to pay anything like market rents for all that land that roads sit on.

Shifting some of that state spending to cycle infrastructure instead of motorists would mean a substantial net reduction in state subsidies.

In short, the main flaw in your argument is that you seem to imagine that the state is currently ‘neutral’, when in fact it massively subsidises driving. People don’t just ‘choose’ to drive too much or in the wrong place, they are responding to incentives created by political choices.

“The terrible Cycle Super Highway in Leeds and Bradford was built predominantly with an EU grant.”

I’m pretty sure it was built with a UK grant from the Cycle City Ambition scheme run by the Department for Transport.

I disagree that current road designs are good enough to get most people cycling, too, although the Leeds Bradford isn’t either.

Joe, I ride my bike every day, including with my kids. Leading by example. I recommend cycling – in the least preachy way I can manage – to friends and colleagues. And do you know how many (or how few) of them are persuaded? Even some of my friends think I’m a bit nutty for riding a bike. But these same people love to cycle in Center Parcs or on a Sky Ride! Many of them say (to me and in every survey on the topic you can find) that they’d love to cycle, but they find doing so on busy roads with fast moving traffic intimidating to the point of scary. Even if you give them stats regarding safety, that doesn’t make the experience pleasant and secure in the way that cycling through a park or strolling down a pavement can be. And to be honest clashes with cars have left me in A&E a couple of times over the last few years so I can’t pretend their fears are completely groundless.

I think everyone on here would agree that bad cycling infrastructure is bad, for the reasons you’ve given. But that’s not an argument against good infrastructure (although there’s certainly room for discussion about what “good” means). The fact remains that we’ve tried “calmly helping people” to get out and about on bikes for decades, and we still have a lower than 2% modal share compared to over 30% of journeys in many areas of the Netherlands. Kids do BikeRIght courses and then get back in the car to go the half-mile home.

Either way, this debate has played out many times on this blog and others like it. I’m sure your sentiments are genuine and well-intentioned, but I worry that this conversation is a little off-topic and getting in the way of more practical discussion.

You could just ignore me, Tim. I won’t take offence. But mark my words, the forces you are up against are monumental. It’s an exercise in futility.

Be sure to update us when you’ve `calmly helped’ your first million (or thousand) people come to that `conclusion’ for themselves. I invite you to think of these constructive suggestions not as bossing, but an opportunity to demonstrate the efficacy of your proposal.

In the meantime, we note that you haven’t managed to refute Ijon’s point.

As for being ‘bossed around’ I don’t need to google it, I feel it first-hand, when being obliged to live in an absurdly car-centric environment. But that sort of bossing is OK with you, I guess, for some odd reason.

I don’t feel bossed around by a “car-centric environment”. The miles and miles of stationary vehicles I pass / filter through on my way to work in the morning and back home in the evening are usually merely a source of amusement for me.

The abuse I get from frustrated car drivers for simply being on my bike? Sticks and stones, mate, sticks and stones!

Problem is, these people will go on to burn every last drop of petrol, if ,we don’t start to boss them aropund a little.

I wasn’t talking about what _you_ feel! I certainly feel ‘bossed about’ by being obliged to choke half-to-death on some of the most polluted roads in the country, and by constantly finding (increasingly oversized) cars in my way, whether I walk, cycle or use a bus. I feel ‘bossed about’ by environments that are invariably organised for the benefit of those in cars (something that is apparent just as much when being a pedestrian as a cyclist, if not more so).

The ‘policy’ that has extinguished cycling as a mode of transport in Britain? Sounds great!

Very interesting! But of course an actual Dutch network would also have a lot of ped&cyclist-only links between those cul-de-sacs (for motorists anyway), and between cul-de-sacs and the main roads (which would have cycle paths of course). So while reading this, I hoped you would also highlight those, both the existing ones (whatever state they’re in…) and the ones still needed. Is that part II? 😉

Yes, there are lots of those: actual and potential. They are generally substandard: too narrow, poor visibility, lack signage and even have ‘no cycling’ signs. They get blocked off by new developments.

If the councils had a policy of requiring proper permeability, it would be pretty cheap and easy to make significant improvements in parallel with new developments. More people would walk and cycle and neighbourhoods would be more pleasant.

The problem is partly a lack of interest and partly that, despite best pracitce guidance (eg in Manual for Streets) there are active policies which end up restricting permeability.

The police cite their Safer by Design manual; the developers cite ransom strips, existing residents object to non-residents using ‘their’ cul-de-sac; there is pressure to maximise the number of houses fitted on to each site; councils want to use section 106 funds for things other than cycling.

Not given up on this one, but there’s still a long way to go on selling the benefits to the decision-makers.

I was back where I used to live as a teenager a couple of months ago. As far as I can see every single lane I used to use, as a pedestrian, to get between large housing estates has been closed. When I asked why the answer was the residents complained. They got them closed because the didn’t like ‘youths’ hanging around and I’m sure coincidentally at least one person got a large boost to their garden by taking over the public laneway. This is a problem because there is no advantage to permeability for someone who only wants to use their car.

My parents house has a lane that goes behind their house. This lane passes between two housing estates and links two main roads. It is about 8m wide and has a tarmac path with grass at both sides. Residents demanded that the council close this because of anti-social activity. They claimed a number of rapes had been committed. My parents argued against this and when they queried the rape allegation the police said that there was no record of any rapes in that lane, and in fact no significant anti-social activity.

If this lane was closed pedestrians would have to follow the road to get to the shops instead adding about a kilometer to their trip. About 40 residents would be able to extend their gardens by 8m. For a car dependant resident there is no advantage to having this lane, they will just drive anyway. They might get behind converting the lane to a road, but if you can’t drive on it what’s the point. There is a significant benefit to closing the lane, mostly that they get a nice free increase in their property value from the public purse and slightly that they don’t have to fear that someone might be walking or hanging around near by.

Sounds odd in that all it would take would be one resident claiming these paths as public rights of way and they would be protected

Think you may be underestimating the challenges of those “secondary distributors” which take traffic from main rds to the culdesacs. Often they don’t have width for bike infra and/or are used for car parking which politically is untouchable. This leaves the only option as being bus gates to filter those streets, not an easy sell in a motorised community.

It is more usually bureaucratic laziness/ contempt for the law in the first instance. The public sector employees who refuse to touch this are completely unelected and the politicians do not get any meaningful say on the matter, not that it would help if they did. Where I live, the district council encourage blue-badge holders to obstruct footways when abandoning motor vehicles on double-yellow lines installed by the county council, with the police force on a standing brief to turn a blind eye to virtually all motoring crime.

It’s really just a question of priorities—at present, moving and storing [mainly private] motor vehicles is deemed most important. But the council do not have a duty to facilitate these at all. If a road can accommodate absurdly wide motor vehicles in one or both directions and/ or motor car `parks’, then it is wide enough for protected cycleways. They merely choose not to provide them, to bolster the convenience of motoring.

Ever heard of don Quixote de la Mancha, anyone?

Cervantes’ character gave rise to the term “quixotism” – which serves to describe an idealism without regard to practicality.

The antonym of this phrase, could (quite neatly!) be “On yer bike, mate!”

It’s As Easy As Riding A Bike.

Choose whatever route you like – direct and busy versus indirect and quieter.

Know your rights.

Take your space.

Assume nothing.

See.

Be seen.

There is nothing freer than the bicycle. Go anywhere, however you like. The only mode of transport to which the Science of Transportation is even less relevant is … Shank’s Pony.

Nothing needs to be done, no money needs to be spent. People may eventually come around to cycling, maybe they won’t. Who cares? It’s up to them. If they do, the infrastructure investment for bicycles will likely follow. And, yes, it will be REACTIVE, as it always has been. Did motorways get built before the motor vehicle was invented? Did footpaths appear before the origin and destination villages?

We have to accept the reality, folks… because of HUGE forces, people just don’t cycle in this country, and people who do choose to use a bicycle to get from A to B are very much in the minority. It never ends well for minorities when those minorities try to shout above their station, regardless how right they are. Sad, but it’s the reality. It ends even worse if the minority somehow manage to get other people’s money spent (badly) on their behalf.

Just deal with it, folks. Hell, most people don’t even WANT to ride bicycles (apart from when the summer sun shines along beautiful forest tracks)! I don’t care what stupid reasons they give, and neither should you.

This is the last you’ll hear from me, I know I’m not… palatable. I came along this path because I do use a bicycle, as I have done all my life, and I like debating lots of subjects, cycling being one of those.

No offence meant, but I have a life to live!

Tara.

Thanks, but I think I’ll just carry on building bike tracks all the same, got kids and all that, seeyah

Thanks, Tom, got kids and all that too (not sure what having kids has to do with this), anyway I teach them that the only thing they owe society is that they and their children are not a burden to anyone, seeyah

And I hope, for your sake, that you had absolutely nothing to do with the woeful Leeds and Bradford Cycle Not-So-Super Highway.

Ha! No nothing to do with me, some consultants in the industry have spoken out publicly at how crap it is, which is unusual.

My kids are pictured on the front of this riding two paths I was involved in building, if you can find anything crap and negative to say about the imagery you win a prize 😂:

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/C2SzHkiWIAAbuV5.jpg:large

infrastructure that serves kids is rarely any sort of financial burden on society. It’s adults who demand infrastructure that their taxes can’t cover the cost of maintaining.

It is not currently reactive. That’s the problem. Even in places where 12% of trips are cycled, schemes to help cycling (whether maintenance or reconstruction) don’t get 12% of the budget and attention. Closer to 2%, if that. It’s not right and it’s worth campaigning.

Pm brilliant summary of the costs of motoring earlier 🙂 are you aware of anyone putting £ to those, to get a summary “the total

Cost of driving one mile is £20 for example 🙂

The total costs of various transport modes is something Ivan Illich covered, possibly in http://www.preservenet.com/theory/Illich/EnergyEquity/Energy%20and%20Equity.htm

There’s the ‘immediate’ cost of fuel, other ‘hidden personal’ costs such as servicing and depreciation, then the ‘external’ financial and environmental costs to society.

Someone made a start on a ‘total cost comparison’ site but I don’t know if it includes all costs or is in a usable state, so YMMV 😉

https://github.com/hdkw/socialspeed/blob/master/README.md

http://codepen.io/hdkw/full/RRGLWR/

Pingback: As Easy As Riding A Bike

Pingback: Transport Myopia – Jason M Falconer