There is a curious opinion that often manifests itself in government and in councils – that a serious commitment to cycling as a mode of transport in its own right can’t be made, precisely because very few journeys are currently made by bike in Britain.*

One of the latest examples of this kind of thinking comes from Reading, where councillor Tony Page has recently argued

We have to balance the interests of all road users and I particularly draw colleagues’ attention to figures which indicate the huge reliance on buses for journeys into the town centre. At the moment, cyclists only constitute three per cent and even if you double that it’s still only six per cent. The dominant and most popular mode of transport is our public transport.

That is – we can’t justify doing anything to improve cycling, because it is a deeply unpopular minority mode of transport, and anyway doing so would probably impinge on much more popular modes of transport.

The problem is that these kinds of opinions are predicated on an assumption that the people of Reading – or wherever – have a free choice about what mode of transport they wish to use. That cycling in Reading is just as ‘available’ to its citizens as bus travel, and the relatively high demand for buses compared to cycling just reflects the fact that people prefer ‘busing’ to ‘cycling’.

But there is of course another way of looking at this situation. It is entirely possible – in fact it is quite likely – that the ‘huge reliance’ on buses for journeys in Reading simply reflects the uncomfortable reality that the form of cycling on offer in the town is very unattractive – unpalatable – to the vast majority of people.

Indeed, it’s a bit like serving mouldy food, and when people decline it, assuming they prefer to go hungry, rather than eat.

The town of Reading is offering crap cycling, and when people choose a less worse alternative, its councillors appear to be assuming that means people don’t like to cycle, full stop.

Yet we know that people do like to cycle, and that there is enormous suppressed demand for it – demand suppressed largely by traffic danger and road conditions.

Waiting for cycling to materialise out of nowhere before you actually decide to start catering for it is, frankly, idiotic.

There is no clearer demonstration of this than the latest Office for National Statistics analysis of cycling to work patterns in the 2011 census, released yesterday [pdf]. It shows that cycling in Britain is largely stagnant or declining, except for increases in a small number of places (mostly cities) where small steps have been taken to improve conditions.

Before taking a look at that ONS analysis, it’s worth remembering that these are figures only for cycling to work, which will almost certainly paint a better picture than figures for cycling as a whole, for a number of reasons. Children are not included in cycling to work figures; we know that cycling rates amongst British children are lower than average. Likewise, the elderly are largely not included in cycling to work figures, and again cycling rates for this age group are below average. Both these age groups are much less likely to cycle than people of commuting age.

Equally, as Rachel Aldred has recently explained, even unpleasant cycling routes to work can be tolerated, or accepted, more than equivalent conditions for other kinds of trips – because these routes become familiar, and dangers can be anticipated and mitigated.

It seems like people are fussier about cycling environments when they’re not commuting. This makes intuitive sense if you think about it. When I’m riding to work, I know my route extremely well as I ride it most working days. I’m travelling on my own, so I only have to worry about my own safety, not that of any companions. I know where the dodgy bits are, where I need to concentrate super hard. I know the timing of the traffic lights – whether I have lots of time to get through or not. I know the hidden cut-throughs I can take to make the journey nicer. As I’m travelling with the peak commuting flows there’s often plenty of other cyclists around, creating a greater sense of subjective safety.

This certainly rings true for my commute across Westminster that I used to make for several years – I knew what kind of traffic to expect on which sections of the route, what kind of driving I was likely to encounter, where I needed to position myself on the road to avoid hazardous situations, and so on. My route got refined over time, and I became conditioned to dealing with what were initially very intimidating roads and junctions.So the picture for cycling as a whole is likely to be far, far worse than these census figures for commuting. (Indeed, we already know that cycling to work rates far outstrip modal share figures in London boroughs, usually being about three times higher).

The ONS tells us that

In 2011, 741,000 working residents aged 16 to 74 cycled to work in England and Wales. This was an increase of 90,000 compared with 2001. As a proportion of working residents, the share cycling to work was unchanged at 2.8%.

The small increase in the number of people cycling to work in England and Wales was matched by the increase in the number of people working, meaning that there was no proportional change in cycling to work since between 2001 and 2011.

The number of all trips being made to work increased by around 14% between 2001 and 2011, yet for England and Wales (excluding London) the number of trips to work being cycled increased by only 2.2%. That means that cycling to work levels outside of London have fallen from 2.8% to 2.6% over this period. The increase in London masks decline in cycling across the rest of England and Wales.

The picture is just as gloomy when we look at a local authority level –

Of the 348 local authorities in England and Wales, 146 had an absolute increase in the number of people cycling to work between 2001 and 2011. As a proportion of resident workers in the local authority, however, only 87 of the 348 local authorities witnessed an increase.

That means 261 out of 348 local authorities – 75% – saw a proportional decline in cycling to work levels over this period. Cycling to work (reminder – much more resilient than other types of cycling) actually went backwards in most areas in Britain. And these are almost all areas that had next to no cycling in the first place. Bleak in the extreme.

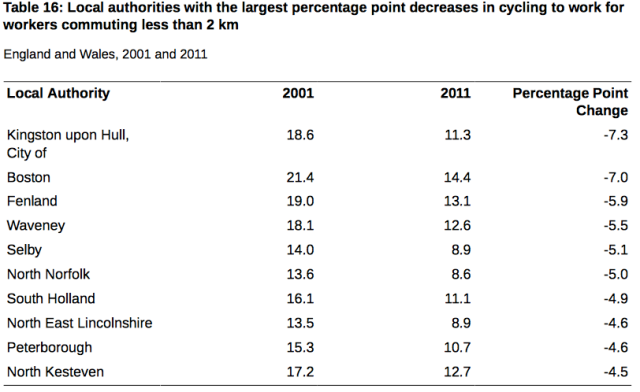

Even places where there was a non-negligible amount of cycling to work went backwards too – among the most striking is (flat) north Norfolk, which had 4.8% of workers cycling to work in 2001. This fell dramatically to 2.8% in 2011. Indeed, it is quite extraordinary how the areas seeing the largest percentage points decline are grouped together in the flattish areas of eastern England.

And the same areas show up among those where short cycling to work trips (less than 2km) have declined the most.

Plainly, no ‘cycling revolution’ is happening in England and Wales. Sporting glory is not persuading people to cycle for everyday trips; nor is marketing – advice, bike breakfasts, or exhortation about how fantastically green and good for your health cycling can be.

Cycling will not grow all by itself, and most likely it will continue to disappear in those areas where it is not being catered for. The idea that these trends can be bucked by expecting people to choose to cycle under current conditions, before we then start to take cycling seriously as a mode of transport, is nonsensical. The investment – serious investment – has to come first, along with proper design guidance to ensure that money is not poured down the drain on inadequate schemes of negligible benefit.

Without this kind of long-term strategic thinking, talk of cycling ‘booming’ in the UK will continue to ring hollow.

*A variant is that the Netherlands and Denmark only spend so much money on cycling because they have to cater for so many people cycling.

Women come up to me and my mummy bike and they ask me where I got it which was locally, we chat and they clearly would like a way to get around that would help them be healthy after having a kid but then it will transpire they live in the next village, which is only a couple of miles away through beautiful fenland. The road has no path and there are fatalities in the paper every week with cars speeding, and overtaking in dangerous places.

I know what I’m doing on a bike, I’ve had some nasty accidents thanks to right turns and car doors but I’ve lived to tell the tale and I know what to do to prevent most things now. I have a massive head start on all those mums who if they were to start cycling now, are in a worse position than I would be learning to drive.

Cycling might as well be banned round here, it’s definitely discouraged, even walking isn’t possible in many places.

Outside of major urban areas, there doesn’t seem to be any compelling reason *why* local authorities should invest in proper infrastructure for everyday cycling. There is hardly a groundswell of public opinion demanding it, politicians are afraid of upsetting car drivers, and so on.

As with a lot of things, it looks like London and a handful of other urban areas are different. Maybe changes to improve cycling in these places will set an example? “All very well in that there London…” is more likely.

First there would actually need to be changes for the better in London. My hope is that the inherent futility in trying to maintain motor vehicle flow in a densely packed urban environment will eventually force TfL to put in proper cycling infrastructure after they have exhausted all other alternatives, but I’m not holding my breath.

Though I am sympathetic to the argument in the article, I do suspect there are very strong cultural issues at work as well. That, as you say, many people just don’t even consider cycling as a possibility. Physical inactivity does seem to have become a taken-for-granted fact of life for many British people – much more so than in some other parts of Europe.

The only thing is, it wasn’t always like this, we got here through some process by which reality and attitudes changed in lockstep, and maybe it is possible to gradually change both back again. So local changes, such as in London or other big cities, might help chip away at those cultural attitudes, both by changing the national political attitude and by influencing other areas at a more grass-roots level (different parts of the country aren’t really hermetically-sealed statelets, even if London feels like that sometimes).

Public opinion is an unreliable guide – ordinary people do whatever is easiest, for much the same reason that water flows downhill – but they’ll resist change, because – from their perspective, it means making things worse before they get better – for them there’s a known downside (I can’t drive everywhere in my car as fast as I please) and a poorly understood upside (what’s this bicycle thing anyway?).

Pretty much everyone here will agree that restricting through traffic on minor roads, imposing and enforcing 20mph limits, and removing on-street parking in places where it causes conflict or denies cyclists a safe route, makes for a better, healthier city with more transport choices. Ask the average man on the street though, and the picture is much more mixed.

The people who oppose these changes aren’t doing so because they’re weak, lazy or morally flawed – they genuinely can’t see a good reason to change. It’s often easier to convince elected officials, who can somewhat see the bigger picture in terms of public health, urban design, collision statistics, community cohesion etc., than it is the general, un-educated public (the same could be said for arguments around the European Union, ahem) – but even then, getting a Labour council (who, with some justification, see themselves as champions of the ordinary and the everyday) to do things that may be seen as making ordinary people’s lives more difficult is going to be an uphill battle.

Result? Policy has a tendency to get trapped in a local maximum.. the easy stuff gets money thrown at it (Southwark council spending a chunk of its cycling budget “upgrading” a cycle facility that’s already one of the safest and most pleasant routes around, and has been for ten years – while doing nothing about the adjoining bits which are full of traffic), but even doing the easy stuff as well as possible and reaping the benefits – as they have in Hackney – doesn’t make the hard stuff any more likely to happen, even though long-term payoff is so much greater.

I agree. Local maxima (or local minima if speaking of disutility!) is the concept that constantly comes to mind with this topic. Made worse by the way it involves both material reality _and_ culture, which reinforce each other in a loop.

We are stuck in a local disutility minima pothole and can’t get out.

The problem here is an issue of goal. You and I might have it as our goal to get more people cycling, for local positions that’s at best an “it would be nice if”. They will just build cycling infrastructure to cater for the existing cyclists. However unfortunate that is, I don’t think it’s ‘curious’. As I said before, from the other side of the matter (Groningen buidling high-grade cycleways to the surrounding towns and villages): Nothing creates political will to provide for cycling like an existing high modal share.

“Nothing creates political will to provide for cycling like an existing high modal share.”

The footnote to the post seems to dismiss this position, but it seems uncontroversial to me. That it is used by opponents of infrastructure doesn’t mean it’s actually wrong. It might be defeatist, but it would be a lot easier to start building a separate cycling network if 20-30% of trips were made by bike.

“But it’s fine – look how many people cycle”, etc…

You’ll notice that infrastructure is often put on streets that already have large numbers of cyclists. You could argue either way, but the further people in power get from having constituents, children, friends or relatives who cycle for practical reasons (or from the practice themselves) the less likely you are to get infrastructure, especially well-designed infrastructure with binding standards.

Not that it shouldn’t be aimed for.

Though one could also note how even streets with very high proportions of cyclists get surprisingly little infrastructure for them. Even London roads that have a majority if cyclists during rush hour get pretty poor and grudging recognition from traffic planners.

It would be much, much easier to justify building WIDE segegrated cycle tracks (and more cycle tracks that are not shared with pedestrians) if modal share was much higher. Of course it’s a little defeatist to say that, but it’s true. The problem with narrow segregated tracks is that they can only really cater for one cycling speed at a time, and people’s preferred cycling speeds vary VERY dramatically. So there is a problem when narrow tracks are built, plenty of cyclists choose not to use them (because their design doesn’t allow for normal cycle commuting speeds), and then car-driving taxpayers mumble and moan that their money is being wasted on stuff that plenty of cyclists don’t even use. This is a bit of a catch-22, and I’m not sure what the solution is – how does one explain that a width of 1.5 m is too narrow to cater successfully for a cycling modal share of 10% to a politican who imagines that cycle tracks only need to be 3 or 4 metres wide in places where the modal share is well north of 30%?

It isn’t just ‘car-driving taxpayers’ that are having their money wasted – we all pay for the roads and any cycle infrastructure. If it isn’t fit for purpose it’s OUR money being wasted too. There are loads of roads these moaning drivers aren’t using for their journey too – maybe we can remove some of them, or parts of them from use by motor traffic and convert them to cycle-only traffic…

I disagree that lack of current cycling modal share is the problem resulting in lack of political will to build cycle infrastructure. Thinking like this leads to the chicken-and-egg paralysis that UK cycle campaigning has got itself tied up for many decades. We can’t ask for infrastructure because only a tiny minority cycle, but because there’s no decent cycle infrastructure, the majority will never choose to cycle. Stalemate.

There is zero modal share for very-high-speed rail travel between London and the West Midlands, yet there is strong political will to provide a brand new very-high-speed rail line to generate modal share for this type of transport. The current modal share isn’t the justification, it’s the transport opportunity and the benefits that will bring.

What we as cycle campaigners need to do is stop worrying about current modal share (which is very low for reasons that anyone will happily tell you about) and start pointing out the many and varied benefits to the country of a much, much larger potential modal share.

Demand-driven supply is the worst possible way to drive transport planning. It’s why we currently invest billions in road schemes that only encourage more people to drive, so all roads get more congested, so we build more roads, and on, and on. Transport should be planned based on the desired travel choices and the efficiencies and costs to society of each transport mode.

I’ve lost count how many times I’ve heard “oh, I wish we could cycle, but it’s too dangerous”. And where safe cycleways are provided (e.g. Bristol-Bath, NCN2 along the coast between Shoreham and Worthing, etc.) the number of people using bicycles to travel around locally goes up incredibly fast. Build it, and they will come, I promise!

I’m starting to wonder how the cycling environment in Lincolnshire has got more hostile to cycling in the last 10 years. While I don’t doubt the lack of infrastructure I do wonder if there’s another reason for the decline in cycling – after all, high-quality cycle tracks haven’t been ripped up and replaced with motorways. Also, London as a whole has not seen a rise in the infrastructure and environmental changes that are thought to be needed to grow cycling, and yet it has grown ‘by itself’. Why is this? What is happening in London that is not happening elsewhere?

Stevenage is a good example of somewhere with good infrastructure but low modal share. Why? What else is happening that stops people getting out of cars and onto bikes, even when it is safe and easy, and how can this be changed and applied elsewhere?

Are these two sides of the same coin?

In Stevenage it remains convenient to travel by car. Since good connections by road remain everywhere. Also I understand that the cycle infrastructure has not expanded out with development. Yet the roads have. Safety of a bike journey is measured by its worst section.

Conversely in London is is often no longer convenient to travel by car. Regular congestion has demonstrated the benefit of making journeys by bike irrespective of infrastructure.

I think Carlton Reid answered the Stevenage question in one of his blog posts, looking at the visionary designer of the new town and his enthusiasm for cycling. In a nutshell, while he made it (relatively) attractive to cycle, he also made it exceptionally attractive to use a car, in an era when car use was exploding and the aspiration of every young adult was to own a car. Wide, straight, sweeping motor roads ensured fast and easy car travel.

Much the same can be said of Milton Keynes. The cycle paths there struck me as pretty mediocre in fact, but there are quite a few of them and they are fully separated from the roads. But again, the road system was conceived to make driving easy, and the place sprawls something rotten making the physical effort of walking or cycling relatively unattractive.

I believe the Netherlands in particular, and other northern European states to a lesser extent, went hand-in-hand with a strategy of making cycling more attractive and driving less – partly that is about higher taxes on cars (eg Denmark) to make them more expensive, but mainly by road design which forces cars to take the long way around on the major distributor roads while walkers and cyclists can cut through the short route by “filtered permeability”.

I don’t really understand why we can’t do more with filtered permeability here than we currently do. The London Borough of Hackney is – rightly – proud of the steps it has taken in this direction, albeit that it can be criticised for dismissing other measures such as segregation on main roads. Local campaigners such as Jon Irwin in the Furzedown area of Wandsworth are petitioning for experimental, temporary permeability schemes to cut rat-running and – if residents conclude they like it – getting the changes made permanent. But, in many places especially in the suburbs there is a fear of increased crime, presumably because people think drug dealers on their BMXs will use the permeability to evade detection by the police who, by and large, keep their lard-arses firmly glued to the seats of their patrol cars these days.

This fear of crime doesn’t seem to trouble the Dutch in the same way, although I have no doubt that they have the same crime and social issues we do, more or less. I guess they just recognise that fear of crime, like the fear of “stranger danger” displayed by local councillors in response to Jon Irwin’s appeals around Graveney School, is rather less of an issue than fear of being run over by a motor vehicle.

That’s a tad unfair on the police. I see a growing number of officers out and about on bikes recently – it seems they’ve cottoned on to the fact that it gives them some useful extra awareness and flexibility to stop and interact with the community that you just don’t get behind the wheel, and the ability to cover far more ground than is possible on foot.

In terms of suburban idiots stuck in a 1980s mentality with regard to burglary you’re spot on, though. They probably also think the thieves will be after their 28″ CRT TV and VHS machine…

“But, in many places especially in the suburbs there is a fear of increased crime, presumably because people think drug dealers on their BMXs will use the permeability to evade detection by the police”

I think the flip side of this is that neighbourhoods where walking and cycling is safe and encouraged means more people out on the streets in the public space. Is the likelihood of observation not also a deterrent?

You’re asking what is changing so that the cycling rate is still falling.

I don’t think cycling is actually getting even worse in the UK, it definitely loses at some places, but gains at others. But there is of course always a choice of traffic, and cars and public transportation do still improve, so that those are chosen more often – and thus, cycling less often.

Another important point is that a long period of little cycling means that people have no experience with it. That is, people who as a child or a teenager have cycled to school or other places are much more likely to consider cycling an option if they’re an adult, even if there are five or ten or twenty years in between. Thus, children cycling less and less 20 or 30 years ago influences adult cycling levels now.

The picture, as you say, is “bleak in the extreme”.

But then you say:

“The idea that these [downward] trends can be bucked by expecting people to choose to cycle under current conditions, before we then start to take cycling seriously as a mode of transport, is nonsensical.”

I don’t entirely accept this.

Cycling: the way ahead says:

“A large number of potential cyclists are already thinking about cycling today. But they are simply waiting for a sign from the public authorities before they get back on their bicycles along the lines of ‘it’s safe to ride a bike — your area authority is taking care of what needs to be done’.”

You also write:

“The investment – serious investment – has to come first, along with proper design guidance to ensure that money is not poured down the drain on inadequate schemes of negligible benefit.”

I don’t entirely accept this, either.

Cycling: the way ahead again:

“Reproducing apparently effective action taken elsewhere could have negative consequences if the concerted and coherent programme on which such actions have been based is not taken into account.”

Ritt Bjerregaard, Copenhagen’s first female Lord Mayor and former European Commissioner for the Environment, has said:

“The essential thing is to take the first step because, while use of the bicycle is a choice for the individual, it is essential to launch the process by which your city builds on the initiatives and habits of some of your fellow citizens.”

This process is described below:

1. Think in terms of a network

2. Plan the network

3. Study the feasibility of the network

4. Introduce the network

5. Develop the network further “on the basis of priority interventions and a timetable” (the key here is sustained investment)

Roger Geffen from CTC has said that he likes this. “It allows for a certain amount of ‘trial and error’ in delivery,” he pointed out, “which makes sense given that this is bound to happen anyway!”

The trouble with the “trial and error” delivery is this:

1. Paint some lines on the road, but only where there’s enough space not to get in the way of the real traffic, and don’t even consider junctions – it’s too difficult/expensive.

2. Paint some lines on some pavement too, to keep people on bikes out of the way of real traffic, and make riders give way at every side street.

3. Point at all these “cycle lanes” that people won’t use and conclude that building safe cycle infrastructure is a waste of money because people don’t even use the stuff they’ve been given.

A better way to create a high-quality network is to study success stories and replicate best practice. This involves a shift from ‘maintaining traffic flow’ to deliberately reducing motor traffic flow in favour of cycle traffic. If this is done it makes it easier to introduce filtered permeability, which makes cycle journeys quick and easy when compared to using motor vehicles. This gets the ball of modal share rolling, and allows further steps to high quality, prioritised, integrated segregation because you’ve already destroyed the “but it will cause congestion” argument by saying “yes – we know. Get a bike – it’s faster and easier.”

It simply isn’t possible to have a high quality cycle network whilst trying to maintain traffic flow, and this is an issue of political will, not investment.

I’m a Reading resident.

Tony Page is probably the biggest barrier to cycling in Reading, his comments are very much those of somebody that used to be the chairman of Reading buses. He has been on the council since the 1970s but then blames previous administrations for cycling facilities that run out suddenly etc.

I’d like to find a way to get him out but I’m not sure where one starts….

Pete

A better way to create a high-quality network is to study success stories and replicate best practice.

What about Portland? The modal share of cycling here has increased by something like 400% since the year 2000. To a large extent this has been achieved with basically just a “bare bones” network. Now they have established this solid base, the long-term goal is for a bike share of around 25%. Crucially, this policy has good political and public support. Roger Geller, Portland’s Bicycle Coordinator, has said: “Every indication we have—from user surveys, use itself, and voting habits—suggests that Portlanders staunchly support Portland as a strong and strengthening bicycle city.”

What about Seville? Jose Garcia Cebrian, head of urban planning and housing at Seville city council, took the view that for any city-wide cycle project to be a success, “cycle lanes had to form a joined-up network that people would really use”. Cebrian approached Manuel Calvo to help design and rapidly implement such a network [my emphasis].

Ricardo Marques Sillero from Seville’s cycling group A Contramano said that getting the basic network to work very quickly was one of the keys for their success in Seville. “Sometimes politicians want to check first if the idea works,” he observed, “for instance making one or two isolated bike paths before making a stronger decision. But isolated cycle paths are almost useless if they’re not connected, making a network from the beginning. Therefore people don’t use them, and the politician becomes disappointed.”

Or what about Darlington? Darlington has the unique distinction of having been (concurrently) both a Sustainable Travel Demonstration Town and a Cycling Demonstration Town. The Guardian suggested in an article from 2006 that Darlington was “the crucible of a grand experiment”.

“What we would like to get out of the Cycle Demonstration Town project,” Phillip Darnton from Cycling England explained, “is the clearest possible indication that investing at European levels will make a real difference to the number of trips people make by bike.”

There was a lot riding on it, The Guardian article noted. “If we’re wrong,” Darnton said, “we’ve blown it completely.”

A big problem is that there is no consensus on how best to proceed given where we are now. Everyone, I think, is agreed on where to end up, but how to get there?

Because there is no consensus within “the cycling lobby”, the decision-makers become uncertain as to the best way to proceed. This uncertainty makes them cautious.

Take Stevenage as an example. Plan and study the network, yes of course; but this done, get the thing to work, get it up and running. This gives you the momentum which you recognise as important, and which allows you to take ever more bolder steps towards a more cyclised environment.

You mentioned studying success stories and replicating best practice. Could you provide us with an example from somewhere that you know about?

To try to build for the future, you must make your foundations strong.

(Robin Hood)

“You mentioned studying success stories and replicating best practice. Could you provide us with an example from somewhere that you know about?”

The obvious example is the Dutch system – a wholesale change in the ethos of transport provision and long-term investment to ensure sustainability. This long-termism of infrastructure investment was shown to this country during the recent floods in the West Country – engineers from the Netherlands were brought across to assist. I saw a BBC interview with one, who said that the investment in flood prevention was £1bn a year for the next 90 years. This country only ever sets out plans for the next decade, which is how plans get shelved on such a regular basis.

If the ‘£900m over 10 years’ cycle infrastructure plan for London was extended to a rather conservative ring-fenced £100m a year for the next 75 years then there’s the scope to put the work in. “It’ll take too long” is no longer an argument, because you’ve acknowledged that and planned for it. There is also no politically-tied finish date – the project is not going to be that of a government or party, but of the people for the future. There is time for further development of infrastructure created in the early stages that may turn out to not be as good as it could be.

As it is, once the £900m is spent London will be declared a cycling city, despite the huge gaps in infrastructure and transport policy that will still be there when everything is ‘finished’.

Firstly, to (sort of) agree with the first point made: namely that cycling isn’t taken seriously because few people cycle, and then because it is not taken seriously – few people cycle.

This approach has a parallel with the refusal to take cycling (or walking) safety seriously at locations where people – and particularly their children – have been scared away precisely because of the danger there. No “accidents” so no problem, despite the fact that a gyratory system / country road with high speed motor traffic obviously has a particulalrly high level of danger for cyclists/pedestrians. (For a discussion see http://rdrf.org.uk/2013/11/15/if-we-want-safer-roads-for-cycling-we-have-to-change-how-we-measure-road-safety/)

You could call both these approaches motorisation Catch 22s.

Now, to present another view about the low level of cycling. You haven’t mentioned:

1. The massive support for car usage. Whether in terms of subsidy and keeping the costs of motoring (to the user) low http://rdrf.org.uk/2014/03/22/the-silence-over-osbornes-hand-out-to-motoring/ or provision of loads of car parking at residences and retail outlets and other possible destinations, or not having to worry about breaking the law, motoring is heavily promoted and facilitated.

2. (In London) a load of support for public transport – which we may need but involves far more in budgets than cycling gets and is thus discriminatory.

3. A lack of support for programmes which genuinely help people who are unfamiliar with cycling: home parking, access to cheap bicycles and maintenance of existing bicycles, access to cheap (over normal clothing) wet wetaher gear and accessories like locks, and giving people proper confidence training as opposed to telling them to wear helmets and hi-viz.

4. A gruesome victim blaming culture with persistent abuse and prejudice against cyclists.

5. Inadequate law enforcement and sentencing against rule and law breaking motoring. You are going to be cycling in the vicinity of motors somewhere allongt he line and could do with the knowledge that inappropriate driver behaviour (for pedestrians and other road users as well, of course) will be dealt with.

These factrs should be considered, methinks, when talking about cycling not being taken seriously.

The five-step process listed above is the Dutch system. They moved to Step 5 very quickly, it is true, but 41 years after they started, they are still making improvement to their cycle networks.

David Arditti has said: “You can’t change everything at once, and it is important to realise how the Dutch got to where they are now. They started by doing the easy things, and that is what we will have to do in the UK. They then kept working on it and improving things, little by little. As David Hembrow always says, you just have to start, and then keep working on it, like the Dutch did. But you do have to start.”

Your view seems to betray a lack of trust. The authorities will do so much, and then, when they’ve done that, they will just stop.

I don’t know how you know this. Regardless, do you actually say that the process which Ritt Bjerregaard said it was essential to launch should be abandoned in favour of something else?

“Your view seems to betray a lack of trust. The authorities will do so much, and then, when they’ve done that, they will just stop”

This is the experience of cycle infrastructure in this country today, as shown by the almost identical 1984 GLC plan for London (seen here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VmR5t2RELns) and the current Mayor’s ‘Vision for Cycling’. This is why I do not trust the authorities to follow anything through. We may be 41 years behind the Netherlands, but we’re also 30 years behind London!

There is no coherent plan for infrastructure – much of the ‘new’ plan revolves around people using roads that are already there and will not change. This is another plan for paint, signs and “keeping your wits about you” that has been shown not to work as a way to encourage cycling in a meaningful way.

There’s clearly a difference between what the Dutch consider a network and what local councils in the UK do. A couple of painted lanes on some roads is not a network. A couple of signs saying ‘share the pavement’ where you have to give way at every opportunity is not a network. A sign saying ‘cycle route’ guiding riders along a route that involves bridges you can’t ride over and gates where you have to dismount is not a network. Yet this is the best we ever get. This is why I don’t trust the authorities.

I hadn’t actually watched that video before, so thank you.

It was the interview with the Head of the Cycling Project Team that most interested me. The aspiration was right, I think:

“The main thing we’re concerned with doing, of course, is implementing cycle routes to help cyclists find their way around London.”

“Our main priority is going to be to continue the routes that we’re already planning, to link up existing ones, to create a comprehensive network for London as a whole.”

He also talked about more ambition with regard to the level of engineering, and monitoring the work of other departments.

All very laudable, and yet it didn’t work out. So what went wrong?

Was the network which they worked so hard to identify ever made to work? The answer to this question is, No.

Why not? I know what I think, but I would be interested to hear what you have to say first.

I’m not sure as to the reasons why nothing happened last time. It could well be the same reason as to why there’s still no joined up thinking across the city – local boroughs are responsible for 95% of the roads and can implement their own individual ideas (or not) which effectively blocks any sort of well-planned, cohesive, integrated network (just look at Westminster now!)

I doubt it was a funding issue, and more likely to be the standard political ‘don’t upset the motorist’ reason why cycling provision is so bad. Those in charge eventually prioritised bus transport instead, with a massive roll-out of bus lanes that cycles are ‘allowed’ to use. This (apparently) means the roads are too narrow for cycle infrastructure, even though most are wide enough for 2 buses to pass each other even if there are cars parked…

I think London has the advantage that most other methods of transport are deeply unpleasant during rush hour. Driving, tubes and buses are all horrendously congested or crowded, which is one of the reasons there is a higher share there. There isn’t a good choice to travel to work (although the transport is great outside the rush hour. Now I’ve moved to Kent I miss it dearly.)

Also, expensive. The tube is ridiculously expensive while buses are just astonishingly slow and unreliable during daylight hours (overwhelmingly due to congestion caused by cars).

Which, come to think of it, suggests the strongest force for more bike use may be increasing population and more overcrowding! The more crowded this country gets the more it will become apparent, surely, even to the dimmest petrolhead, that bikes take far less roadspace than cars. There just isn’t enough room on the roads to _not_ have decent cycle infrastructure.

One issue not commented on so far is the bias of the census against mutlimode trips. If I do a walk-bus-train-walk commute, it counts as a train journey if that is the longest leg. Likewise bike-train-bike is a train journey. In 2001 St Albans station had few cycle stands and small numbers of cyclists. There are now 1000 stands and they are full. Yet this isn’t counted in the census. If you asked for the main form of transport and how you got to it you’d get massively different stats.

Adam

I dont think the drop in cycling to work rates in North Norfolk or other (flat) – and flat is subjective – areas of East Anglia is necessarily related just to problems with cycling infrastructure.

one of the things we need to understand is whether in those areas there are enough jobs of the type that would enable people to commute comfortably enough to by bike in the first place are available.

As I suspect its really the decline of those jobs in the last decade in the East as many of the traditional industries in that area have ceased to operate, that forces people to seek other forms of transport to make their now much longer commutes to jobs in the bigger towns/cities across that region.

Anyone who calls North Norfolk’s coastal chalk ridge “flat” has never ridden a bicycle along the Cromer Ridge to Beacon Hill. It’s no Alps or even Peak District, but it’s not flat… but that’s not the reason cycling is going backwards there in my opinion. It’s funding, which I think works out at something under £2 per person per year, spread over too many small towns and villages. Which makes neighbouring West Norfolk (half of which is flat) a notable absentee from that list of biggest falls because it has the same underfunding and similar terrain to Fenland and South Holland which are among its other neighbours.

I think cycling is still holding up in West Norfolk because the main town (King’s Lynn) is much nicer by bike than car, with some provision you could call almost 1970s Dutch: basically the stuff you criticise as the bad bits, but still better than most English towns. There is a feeling of slow decline, though, as the cycleways get more potholes, more root damage, less mowing and so on, plus there’s more conflict at the road crossings (which are rarely grade-separated) so we must challenge this underfunding now, before we go the same way as the neighbours.

Awesome! Its truly amazing post, I have got much clear idea regarding from this article.

Pingback: Singletrack Magazine | The Lion's Share

Pingback: The Lion's Share | Singletrack Magazine