Pedalling into the Dutch city of Delft last Tuesday I went past a branch of Albert Heijn, which is (approximately) the Dutch version of Waitrose – or at least, a supermarket at the slightly higher end of the Dutch price scale.

The branch of Albert Heijn on Ruys de Beerenbrouckstraat, Delft – with the city centre Oude Kerk in the distance, about 1km away.

Naturally enough I stopped to have a look at was occurring, an easy thing to do given that the cycleway along this road runs right past the supermarket entrance.

At about 10:30 in the morning, the front entrance was heaving with bikes – people shopping in ways that they would do in the UK, but loading their goods onto those bikes.

There was a mum loading a trolley full of goods (and her children) into her cargo bike.

And other people loading the contents of trolleys and baskets into their panniers.

And other people loading the contents of trolleys and baskets into their panniers.

What was fascinating to me was how all the space in front of the supermarket was completely dedicated to people arriving on foot, and by cycle. There was no parking for motor vehicles anywhere in sight.

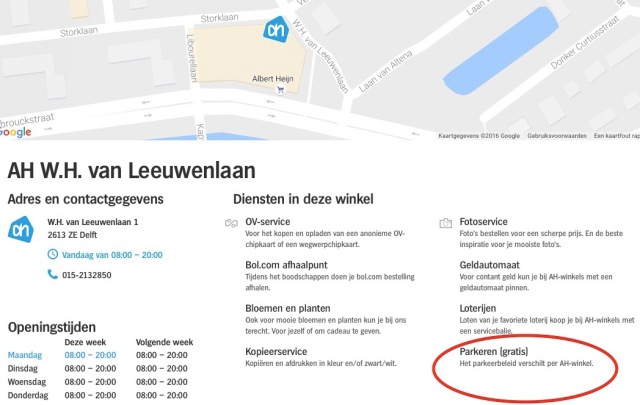

But that, of course, isn’t quite the whole story! There is car parking at this supermarket. It’s just that it is hidden from view, on top of it, with an entrance around the back.

And it’s free, all day long.

And it’s free, all day long.

Interestingly, the location of this supermarket is given as the minor road the car parking entrance is on, not the main road where people walking and cycling will gain access from.

This is despite this supermarket being in a city-centre location. There isn’t anything to stop you driving to it and parking above it, at no cost (save for your fuel).

So in many ways this supermarket is actually a microcosm of the Netherlands in general. You can still drive to the supermarket, with ease. There probably won’t be a queue to get in and out of the car park, because so many other people will be cycling to it. The parking itself will be free, even at peak times. In these respects driving in the Netherlands is actually easier and more ‘available’ than in Britain. If you wish to drive your car, your journey will be more attractive, and cheaper, simply because so many other people aren’t driving.

What does make the difference is the way that cycling to the supermarket is extremely painless. The people arriving here by bike will have started their journey on quiet, access-only streets, and then pedalled along the main road in comfort, safely separated from motor traffic.

Planning is also a factor here, in that the Dutch does not really have out of town supermarket shopping, which would clearly make cycling more inconvenient, adding distance to ordinary shopping trips, and making the car relatively more attractive. It also makes smaller (more cycle-friendly) shopping loads an easier prospect, if your supermarket is close at hand. Daily shopping, for instance, is much easier when your supermarket is not out of town. Dutch supermarkets have to be within urban areas – but at the same time that doesn’t stop them from offering free car parking to their customers.

Mainly, however, people choose to cycle in the Netherlands not because driving has been made inordinately difficult – it certainly hasn’t in the case of this supermarket – but because cycling has been designed for, has been made a safe and easy mode of transport, so much so that it naturally becomes an obvious choice. It’s simply easier and more convenient than driving, right down to the way you can arrive at the front door and park, rather than having to take your car around the back, and upstairs. It’s very much carrot, rather than stick.

It’s the way to go. Make it easy to use non polluting transport and the population becomes healthier, less overweight. Air quality increases and health services are more available to the wider population – not weighted down with dealing with inactivity related illnesses.

This example illustrates both the power and the limits of ‘build it and they will come’: many people will choose to cycle given a good combination of cycling infrastructure and accommodating town planning, but even then driving is still sufficiently appealing to many that it is profitable for a retailer to build in underground parking – a considerable expense. Hence the citizens must still breathe the fouled air (Dutch air being some of the dirtiest in Europe), devote considerable shares of valuable urban space and infrastructure budgets to accommodating private motor vehicles, and watch their fellow citizens warm the planet even though safe and convenient cycling has been provided for. All readers of this blog are surely fans of improved cycling infrastructure, but we should not lose track of the fact that research comparing Dutch cities indicates that costs imposed on drivers – e.g., though parking charges – is also an important factor in raising cycle share.

A link to the research would be useful. Some readers may not have come across it.

There are two research papers I’m thinking of – they’re mentioned in this blog post:

The problem is that car parking in Dutch towns and cities is, typically, *substantially cheaper* than in equivalent British towns and cities, because demand for that parking is much lower. That suggests that car parking charges are really quite a negligible factor in determining cycling levels compared to infrastructure.

Two problems with this comparison:

1. Price of which parking? The price of parking in UK towns is high if you park on the street. It is not high if you go to a superstore – there, it is usually free to the consumer. And, since the planning process in the UK has been friendlier to out-of-town superstores (which have cheaper land available for parking), “free” parking also costs retailers in the UK less to provide.

2. The effect of the parking price depends on the alternatives available. In most of the UK, as we know, it can be miserable, time consuming and even dangerous to get to your shop of choice without a car. So even if parking is expensive, you’ll drive (though once you’re in the car you’ll likely go to a superstore with free parking). In the Netherlands, the cycling and walking alternatives are much more attractive, which can mean that a price of parking that looks low by UK standards could still enough to dissuade many Dutch residents from driving.

Now, the story I’ve just told (item 2) says that cycling infrastructure is important (otherwise, a low price of parking wouldn’t do much to discourage driving); the question remains whether the price of parking is important as well. This is where the sort of studies I linked to in my blog are helpful. They make statistical comparisons between large numbers of Dutch towns, which have different levels of commitment to cycle infrastructure, different levels of cost imposed on driving/parking, different geographies (hills, overall population, population density, wind), and different demographics. All of these things can (and, it turns out, do) affect cycle share. To figure out how much of an effect any one of these factors has, you want to be able to control for the other factors. And, it turns out, comparing between Dutch towns, both cycle infrastructure *and* costs imposed on driving or parking are important for raising cycling share. The statistics in these studies aren’t the best, due to limitations in the data, but they are far better than making between-country comparisons based on one variable, or extrapolating to all of the Netherlands based on one town.

1) Parking is free at Dutch superstores too. It’s also free in inner city locations, like the supermarket in this post. And Assen – which has a substantial cycling mode share of around 40% – has free parking, right in its city centre. I’m not sure this is a helpful argument for you!

2) This I agree with. I suspect Dutch people are more sensitive to the price of parking given that the alternatives to it are attractive. (This also explains why Dutch car parking tends to be lower than the UK, or even free, in equivalent locations).

I don’t dispute that the price of parking is *a* factor in whether people are inclined to drive. If parking costs £100 per hour, for instance, that will clearly discourage people from parking!

But if we compare Town A, which has excellent cycling infrastructure, a cycling mode share of around 40% and substantially cheaper parking than Town B, which has a cycling mode share of 1-2% and poor or non-existent cycling infrastructure, what does that tell you? It tells you that the price of parking is really quite a negligible factor in determining whether people will be prepared to cycle, compared to a high-quality cycling environment.

I don’t doubt the importance of infrastructure, and if I had to choose just one intervention I’d go with the infrastructure. But I do think you’re sticking to a method of comparison that makes infrastructure look like the only important thing, and that the method you are using is far from the best method we have. A systematic comparison between Dutch towns can tell you more about this than comparing between general pictures of the UK and the Netherlands, because you can control for more factors: within a country, the towns have more in common to begin with, and the same things tend to get measured in the same way. I’m simply telling you what such statistical comparisons say: the cost of using a car is also important.

Also, frankly, I think that too much of our knowledge about Dutch cycling comes from Assen, thanks to the worthy evangelism of David Hembrow. Assen is a relatively remote small city of 67,000, surrounded by fields; the nearest larger city is Groningen, a university town (also remote) with a colossal cycling share – this being relevant because even if you commute from Assen to the nearest bigger city, you’d be unlikely to drive. I’m sure these are wonderful places to cycle, but we may learn more about what should be done in British towns by studying the wide range of experience across different Dutch towns and cities – not only small remote ones like Assen and Groningen, but also Utrecht, Amsterdam, Rotterdam and the rest.

Improving cycling infrastructure (including closing rat runs) is much more politically realistic than congestion charging. There’s only one place in the UK which even pretends to have a congestion charge, inner London. But even that doesn’t charge for congestion as it’s a day ticket. A congestion charge would be mileage based, charging a higher rate at congested times.

Also congestion charges are regressive taxes. Isn’t congestion charging just an off-shoot of Neo-liberal “markets solve everything” dogma?

“I do think you’re sticking to a method of comparison that makes infrastructure look like the only important thing”

This is the point though, isn’t it? If Town A has cheaper parking than Town B, yet Town B has essentially no cycling while Town A has a 40% mode share with an excellent cycle network, what does that tell you about the relative importance of the price of car parking versus the quality of a cycle network?

(Your comments about Assen are largely wrong – as J Eldering has pointed out, very few people will be cycling between Assen and Groningen – the cities are more than 15 miles apart, and are entirely distinct entities, with their own very similar mode shares, independent of one another. It’s also worth pointing out that, yes, parking is cheap or free in other Dutch towns and cities. I will do a compilation post at some point in the future.)

This is in reply to Frederick’s reply below, it’s too deep for me to reply to.

I’m not trying to get involved in the argument of how much parking costs contribute to cycling share; let me just say that I agree that proper statistics are useful.

Assen may not be that big, but I think it is quite representative in size for a Dutch city, and by itself it actually fulfills a hub function for the region: talking about commuters from Assen to a larger city sounds strange to me. Also, I think that of those few people that would commute from Assen to Groningen would typically do so by car or train. Very few Dutch people would consider the distance of 30 km short enough to do this by bicycle.

@George Riches

“Also congestion charges are regressive taxes. Isn’t congestion charging just an off-shoot of Neo-liberal “markets solve everything” dogma?”

But I don’t think it makes sense to insist that markets are always wrong, either. I think they at least offer a starting point.

What you highlight is the inconsistency whereby the same folk who insist you have to have markets for everything else, want the most dubious kind of socialism when it comes to the roads and driving.

Public transport must pay its own way, sugar must be taxed for the public health costs it creates, water supplies must be privatised, students must pay for their degrees, they will insist. Nothing should be provided free unless absolutely essential (because otherwise it will be used wastefully and resources will be misallocated)…

Yet most, though not all, who propound those views take it for granted that, in their capacity as drivers, that their wasteful use of scarce road-space (never mind the huge pollution costs they impose) has to be provided completely free and unmetered.

Even if its being used purely for storage.

Also, congestion charging can’t be said to be _entirely_ regressive, when the situation is still that the wealthier people are the more they drive, and the poorest don’t drive at all.

Clearly though such charging needs to go hand-in-hand with providing alternative, and objectively less costly, forms of transport.

Highways Engineers have been known to use cyclists as some sort of mobile traffic calming – inserting road narrowings in the hope that the presence of a cyclist in the narrowing will cause motorists to slow. Instead people are deterred from cycling.

Using cycling as part of a wider anti-motoring agenda does lead some people, who both cycle and drive, to draw away from cycle campaigning.

What you say about bad infrastructure – choke points like that – can also be said about a lot of good cycling / pedestrian infrastructure: often the steps that are needed from a strictly pro-active travel (not anti-car) standpoint do slow cars down at junctions, or reduce the amount of road space for driving or parking, or eliminate through traffic on local roads. If you remove these tools there’s not much you can do in a crowded town to make it safe for cycling. They can always be presented in a positive, pro-cycling way, but it is neither surprising nor irrational that many drivers see these measures as anti-car.

I suppose you’re saying that additional measures (such as making parking more costly, or refusing to expand motorways) bring on even more opposition. I think that position is the political logic behind an all-infrastructure, build-it-and-they-will-come cycling strategy.

Where to come down on this depends in part on why you’re campaigning for cycling. Do you want better cycling infrastructure only so that people who happen to prefer to cycle – you and yours, perhaps – can do so safely? Then positive-only might make sense. Do you want it because you believe, for whatever reason, that the cycling share should rise? Then, the lesson from the Dutch studies is that this depends not only on infrastructure, but also on the cost of using a car; where raising cycling share is the objective, it’s one thing to avoid antagonizing people unnecessarily, it’s another to ignore the fact that the cost of driving does matter. Finally, do you support cycling campaigns at least in part because you think that reducing automobile use is important for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, independent of whether cycling increases? This last one is my position: I prefer to cycle, but if all those drivers took the bus, I’d be happy as a clam, because they’d be producing so much less CO2: so I do care about reducing car use per se, and I know that many will find that negative.

But, for *any* of these objectives, it is also worth considering the limits to a strategy which reduces road capacity for drivers (slowing traffic, space for cycle lanes, hierarchy of provision) without reducing the pull-factor of destinations, like Ikea and Tesco with ample free parking on the outskirts of town. Reducing road capacity without reducing the pull factors is a recipe for congestion, and there is not much that people like less than being stuck in traffic. People may react badly to the idea of any policy that sounds “anti”, but they may react even more badly to actual congestion. And, however negative it may sound negative to suggest raising the price of parking, in fact on-street parking near many British high streets is already highly taxed. The problem is that superstore parking is not; the failure to tax superstore parking is the source of a million rat runs, a lot of dirty air, and the decay of the high streets.

You wrote: ” prefer to cycle, but if all those drivers took the bus, I’d be happy as a clam, because they’d be producing so much less CO2: so I do care about reducing car use per se, and I know that many will find that negative.”

So if the cars went electric, with the current produced from renewables, you wouldn’t mind cars?

No matter their danger, the space they take up and the disadvantages to those unable to drive? Bit inconsistent?

I think there are lots of problems with cars – I don’t like the danger to other road users, I don’t like the whole urban experience that results when cities are designed around cars. So, no, I wouldn’t be happy with them even if they were zero-emissions. But global warming trumps all the rest, by a couple of orders of magnitude, so if one had to choose…

Also, I say zero-emissions, not electric. Until the electricity supply is effectively zero emissions (which it may never be but now it’s not even close), electric cars are nice mostly because they reduce local air pollution; for GHG reduction, ride a bike or take the bus.

Hello Frederick Guy

You said that Dutch air is some of the dirtiest in Europe. I had a look at a map based on a WHO report on air quality and it looked like the Netherlands was fairly typical for Europe (http://aqicn.org/faq/2015-05-16/world-health-organization-2014-air-pollution-ranking/). Was there some other data you were thinking of?

Hello Stephen Watson,

I think you’re right, actually – I don’t know what map I’d been looking at, but your comment has sent me checking and though it varies by type of pollutant overall the Dutch picture is fairly typical for western Europe. Thanks for pointing this out.

There’s nothing stopping us from using multiple methods to discourage car use, make things safer for everyone, give genuine choice to as many as possible and reduce the harms of cars. We can of course go and transplant the methods the Dutch do in terms of street design and this is the most important method by far IMO.

We can also make car parking mostly pay parking outside of your own private residence if you own a driveway. There are some exceptions though, it’s cruel in my opinion to charge people for hospital parking, at least the visitor parking, because people generally do not go to hospitals by their own desires, and besides, if you got shot in the leg, would you be likely to remember to feed the meter? But for a simple grocery store, it’s fine to put a fee on that.

As for addressing air pollution on the vehicle end, you can mandate that biofuel with say a 50% ethanol 50% vegetable oil mix bybrid (it also has an electric battery that is usually relied upon first in the way that gasoline hybrids do too) and electric cars are the only type allowed to be sold say beginning in 2018, offer financial subsidies perhaps for switching, mandate that petrol stations carry biofuel like this as well as high speed charging ports, and equip car parking areas with some portion of them having charging ports, especially the longer term multi hour parking. And you can do things like having municipalities switching to electric buses, companies in the urban or near urban areas can adopt electric vans for their transport needs, etc.

You can also do things to concentrate cars where they can be managed, on motorways that bypass urban areas not splitting neighbourhoods in half, and introduce measures like pedestrian friendly car bumpers.

You can also give financial incentives, especially ones that give out rewards rather than say tax deductions, for say making over 75% of your utilitarian journeys within 7.5 km of your home via bicycle or walking, and if you use public transport, some public money can go to subsidize the rate for trips over say 7.5 km and even more for trips over 15 km.

Infrastructure is by far the most important, but don’t forget all the other things that we do to encourage car use and discourage other methods.

I thought that if you wanted (a lot of) segregated cycleways you would have to take space from somewhere, normally from motor vehicular traffic. If that’s true, then you ARE going to inconvenience motorists.

In addition to removing space for motoring the pedestrian and bicycle routes also have priority over motorised traffic at most of their intersections. The region used as an example has a strongly hierarchical system of roads to minimise through traffic on local streets further discouraging car use by making its journeys longer. Throughput for motorists is extensively restricted compared to the alternative of paving every open space with more traffic lanes.

Though very unpalatable to a car centric society its the everyday practicality for the Dutch. From the other side bicycle infrastructure is able to carry more people during rush hour, and has a lower fatality rate so it has benefits for society.

But I think you already understand this well 😉

Is the answer not both ‘yes’ and ‘no’ simultaneously?

It takes space from motor vehicles, but if it works, it also takes away demand, and as bikes take less space than cars it would logically remove more demand than space.

The difficult bit is starting the process, I suppose, where drivers see the loss of space before they see any reduction in demand.

Though I do believe there are a proportion of drivers who are just addicted to driving for its own sake for cultural reasons, partly because it gives them a feeling of power and dominance. Just as there are vehicular cyclists for whom much of the appeal is the chance to prove their technical skill and desire to tweak the nose of fear.

Those groups won’t respond linearly to rational considerations about convenience and congestion, and thus make the calculation of incentives and behaviour more tricky.

Hello rdrf

Perhaps it’s worth drawing a distinction between making driving more difficult for the sake of it, and making driving more difficult as an inevitable consequence of doing something else, something that could not reasonably be done any other way. In the first category would be congestion charging for example. It exists purely to discourage driving. In the second category would be removing through motor traffic from a narrow residential street, as this may be the only way of achieving a pleasant and safe environment for residents, as well as good conditions for cycling. As a side effect this also happens to make driving short distances less convenient.

I think that Mark and others are saying that choices made in the Netherlands tend to be in the second category, not the first.

As others have noted, in the long run taking away space from motor traffic for cycle paths is not such a hardship for those travelling by car, since each person cycling means fewer cars blocking up the road. Also, I think having bikes and cars separated on main through routes is much less stressful for drivers.

Looking at the bigger picture, I believe that if our energy consumption is to be sustainable, we must substantially reduce the amount of driving, using measures in “category 1”. But this is a separate objective from making cycling attractive and accessible to all. When the time comes to making driving much more difficult, a country where cycling is an established alternative will be in a better position to do so.

To put it another way, to make cycling an everyday mode of transport for most people, I think we need mostly carrots. To be sustainable, I think we will need some sticks too.

In many places, motorists are inconvenienced already, due to the numbers of them; they are part of the problem. And as nobody knows how many people would ditch the car for shorter distances if they could cycle safely, this means city-planners have to take a gamble. In Denmark and The Netherlands the cycle never disappeared totally from the streets, so it was easier for these countries to give more space to the bike.

My father cycles daily to his Albert Heijn in the village, unless it rains a lot or the roads are icy, in which case he uses the car. The car park is tiny and on those days there is usually a queue to get a parking space. At 89 these 1km cycling trips keep him healthy. He makes a point of not buying more than he needs for that day, so he can go again the following morning. He is not an exeption, and he certainly doesn’t feel a hero (he is in his sons’ eyes!), but he feels priviliged that he can still do this. A lot of people his age have had to give up cycling because of ailments of old age. The loss of the ability to cycle is generally felt as quite painful, at least as distressing as having to give up driving. My mother, 90, has gone electric and still ventures out to the market in the next village. As children we worry about how long they will be able to keep on cycling rather than about their safety on the road. We take the safety of the cycling environment as granted (well, living in Britain, I appreciate it a bit more than my brothers!). I think we worry more about them still driving…

The Albert Heijn we used on the edge of Nordwijk seemed to be out of town style. A car park right next to the shop all at ground level. But compared with UK the car park was probably not anywhere near as big. And while the car park was near the entrance, just like in your picture the area immediately outside the entrance was pedestrians/cycles.

Is it this Albert Heijn: https://goo.gl/maps/SXCKSNQ8Tur ?

That is a typical 1970’s neighbourhood supermarket. The neighbourhood it’s in, the Beeklaankwartier has 5000 inhabitants, and it’s quite common for neighbourhoods that size to have their own supermarket. If it wasn’t there people would have to drive to the village center for to get their food.

The number of parking spots can be decieving since the supermarket is located in the center of a neighbourhood. Many of the parking spots are used for residential parking or to visit the dentist across the street. And when you start counting the bike parking spots you see there are 96 of them, all used to go to the supermarket, while there are only 20 or so car parking spots near the entrance.

When building a neighbourhood Dutch planner also plan the number of parking places. The land price here is low enough that building roof parking isn’t worth it.

Uplifting and dispiriting in equal measure. Great to see such common sense being applied to what are everyday tasks. Depressing to think this won’t happen in Ireland anytime soon…

In contrast, here’s Ifield in Crawley, where cycling up to the shops is prohibited. It’s even illegal to cycle to the cycle racks.

https://www.google.co.uk/maps/@51.1220284,-0.212401,3a,75y,297.11h,77.54t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1sEv3Oz3uoQUqFCBxD-p6LFw!2e0!7i13312!8i6656

For Tilgate in Crawley, the council went even further and moved the cycle racks as far from the shops as possible; motorists have parking priority there.

Whether it’s coincidence or correlation, the supermarkets in Britain where IME you’re most likely to see many bikes used are Waitrose and Aldi.

Any comments on my comment above? E.g. that if you want to create Space for Cyclists you will have to inconvenience motorists and thus use stick as well as carrot?

UK motorists often tell us how enjoyable it is, usually as a precursor to dissembling about why they could never consider cycling themselves. Surely having to travel the long way around for local motor journeys would be welcomed as an opportunity to do even more of it (carrot) than an inconvenience (stick)?

I wonder how far the carrot has to go before that works in the UK as theres a suburb/estate I know locally that has pretty good (well good for the UK at least) cycling provision, theres several traffic free routes through the estate, and it links up all the houses with schools and supermarkets etc, its well signed and reasonably well maintained. Sustrans once measured 61% of pupils at the local high school cycled, though I believe that figure has dropped significantly of late.

this week there have been fairly major road works blocking the main through road, that connects the estate to the rest of the local area, and its caused absolute traffic chaos the local newspaper is on its 5th article in 2 days about it, with people reporting 5mile journeys taking 2hrs, that kind of thing, and all the residents on the estate are now demanding some form of bypass or relief road.

the problem is alot of those 5mile journeys all seem to be journeys within the boundaries of the estate, literally people on the estate driving their kids to the local schools on the estate, or popping to the local mini supermarket,or driving to the local gym…all of which could even be walked, let alone quite easily cycled and never a car or hairy road traffic problem encountered, and yet they are still all using their cars and then moaning about the congestion its causing

which makes me wonder if the UK will ever get it

The only time I’ve felt truly safe cycling everywhere with my kids was when we visited Amsterdam and Groningen earlier this year. I’ve tried to cycle everywhere possible with them in the UK – school, supermarket, leisure centre, play dates etc, but sometimes it’s just not safe to do so, especially as they get older and want to pedal themselves. In Amsterdam my 9 yr rode around at rush hour with absolutely no problems – something I’d never be able to let him do here in the UK. More info on how the difference felt to me, is here: http://www.cyclesprog.co.uk/blog/im-not-weird/

Then there’s the ride-through supermarket!

Thanks for your answer Stephen Watson: “Perhaps it’s worth drawing a distinction between making driving more difficult for the sake of it, and making driving more difficult as an inevitable consequence of doing something else, something that could not reasonably be done any other way”.

My view is that (at least a lot of) motorists won’ get the distinction. Maybe I’m pessimistic but I don’t think drivers feel that things are getting better if they lose space on the road – they may intellectually “get it” – but worrying about congestion is not about rational analysis of seeing that ex-drivers are now cycling on the cycle track, it’s more about feeling that you aren’t driving as quickly as you would like to be.

I also take the point made that in Denmark/Holland cycling culture never really disappeared so there was some form of cycling habit to get back into.

So my view remains that getting Space for Cycling will involve a lot of drivers feeling that they are on the end of more stick than carrot.

<FX: shrug> So what? Are you expecting us to sympathise with them to the extent that we just give up, or something?

Ditching the “them and us” attitude would probably help too. Does using my car to drive mean that I am one of “them” or does it just mean that cycling in the UK (especially Southampton) is a horrible experience that barely anyone wants to endure due to lack of subjective safety and convenience?

Campaigning “for cyclists” is very inneffective, campaigning and the language used in campaigning needs to refer to the mode of transport, rather than users, and how cycling infra can benefit people. The transport system in the UK should allow people to use the most appropriate mode of transport for each journey, rather than converting “motorists” to “cyclists”.

Well, it might help. But that is speculation and IMO vanishingly unlikely in the present circumstances. Yes and yes—the two are not mutually exclusive. You can read my previous `them’ as `motoring’ if you like, but don’t kid yourself that campaigning for `cycling’ as a mode is any more effective. Not least to the ears of TPTB.

“Them and Us” certainly gets more air time on the radio and more clicks on news websites. But does it get any more cycling?

Seems improbable, but then I never claimed it did. Does unilaterally half `ditching [Mark Small’s alleged] attitude’ get any more cycling, either? Conversely; does cultivating one get any less cycling? Do we have any data, or is it just guesswork all the way down?

You can read my previous `them’ as `motoring’ if you like, too. Stop trying to erect such ridiculous straw-men.

I also wanted to add that I found a free car park in Houten, probably the most bicycle-centric place in the Netherlands! Driving in Houten just doesn’t make any sense.

Pingback: Contested spaces to shared spaces in a car-dominated culture – Urban Cycling Institute

Pingback: Making cycling mainstream: the role of wider policy – Urban Cycling Institute

Pingback: Making cycling mainstream: the role of wider policy – Urban Cycling Institute

Pingback: Contested spaces to shared spaces in a car-dominated culture - Urban Cycling Institute