There was a flutter of excitement at the Cycle City Expo in Birmingham last Friday when Andrew Gilligan mentioned that the important (in many senses) London borough of Westminster would shortly publish a very ambitious cycling strategy, and not just any kind of ‘ambitious’ –

Gilligan said the soon-to-launch Westminster cycle strategy was *more* ambitious than the Boris one.

A draft of that Westminster cycling strategy was duly released this week [pdf], and, frankly, it simply can’t have been the same strategy that Andrew Gilligan was looking at, unless he was being exceptionally charitable. Because it’s miserable. It bears no comparison at all with the Mayor’s Vision.

It should be conceded that this is, of course, a draft of the strategy, and not a final version, but what is presented in the document as it currently stands is deeply uninspiring and half-hearted. In fact it’s not even half-hearted, it’s barely ‘hearted’ at all. I started reviewing it in a generous and open-minded way, but it’s so bleakly awful that I couldn’t help but end up trashing it. In places, it made me genuinely angry.

The introduction starts out promisingly enough, noting that

cycling is something that should be encouraged due to the returns that it delivers to the wider community through reduced congestion on the roads and public transport system, better local air quality [note – Westminster has some of the worst air quality in the country, with limits set by European legislation regularly exceeded] and improved health for residents and visitors.

and admitting that while, some measures have been taken in Westminster to make cycling more viable,

there is still far more that can be done to make cycling safer and more attractive, particularly with the enthusiasm generated through Britain’s recent Olympic and Tour de France successes. This means further investment and improvements are needed to overcome barriers to cycling and to encourage more people to take it up safely.

Here are the first worrying signs – why on earth should the Tour de France have anything to do with making cycling as a mode of transport safer and more attractive in Westminster? And instead of referring to making the act of cycling safer, it is ‘people’ that are being encouraged to ‘take it up safely’ – the burden of responsibility being shifted to the individual. Indeed, this actually forms the main basis of the ‘safety’ strategy outlined later in the Draft; cyclists being encouraged to look out for themselves (and, worse, the way individual cyclists are treated being framed as a consequence of the behaviour of ‘cyclists’ in general).

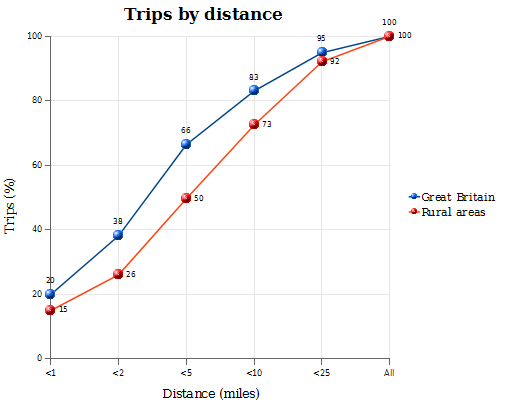

76% of Westminster residents never cycle. Beyond that statistic, there is huge potential for shifting hundreds of thousands of trips in the borough made by ‘mechanised modes’ (car/motorcycle/bus) onto the bicycle, particularly those up to 5 km. Even using Transport for London’s highly conservative estimate of Cycling Potential [pdf], 230,000 daily trips into the borough could be made by bike instead (around a quarter of all trips in, on a given workday). This would obviously reduce congestion on the road network considerably, as well reducing demand on public transport.

As always, the main barriers to cycling uptake are perceptions of safety, concern over motor traffic, and a lack of confidence. This is acknowledged by the Draft, albeit in a slightly mealy-mouthed way –

… there is a school of thought that suggests that safety fears in particular are sometimes over exaggerated as they are perceived as more of a valid reason to give for not cycling, particularly if the real reason is more to do with lethargy. Nonetheless, this tells us that for new cyclists, we must place greater emphasis on making cyclists feel safer on London’s roads, and reducing accident casualties. There is also much to be done to build confidence amongst a broader cross section of society that almost anyone can become a competent and regular cyclist, through training, education and regular engagement activities.

A not-so-subtle hint that those who don’t cycle for reasons of safety in Westminster might be lazy slobs rather than people who are genuinely scared of venturing anywhere near the roads, coupled with an emphasis on ‘building confidence’ as a substitute for actually making the roads subjectively safer. Hardly inspiring.

The Draft Strategy then moves on to ‘challenges’. Having already acknowledged that more cycling would reduce congestion and ‘pressure on the street’, paradoxically the Strategy then suggests it is ‘pressure on the street’ that will make it difficult to encourage more cycling.

[There is] significant pressure on our streets from people arriving and leaving by different modes, all competing with one another and with other modes for limited space on the footways, at the kerbside and in the carriageway – more so than any other borough.

This is ducking the issue, because high demand for limited space suggests an even greater need to shift trips in the borough of Westminster to efficient modes like walking and cycling than would be the case in ‘any other borough’. However Westminster are apparently too short-sighted to realise this, or to even acknowledge what their own Strategy has just stated. Later we have the sentence

Westminster’s roads serve a vital function and it is imperative that congestion is minimised

Again, deliciously oblivious to how more cycling in the borough would actually serve to reduce congestion, not cause it. To repeat, the Draft has already stated this in the introduction.

There follow more unserious attempts to suggest that cycling cannot be provided for –

The narrow, historic nature of many of Westminster’s streets means that providing separate space for each road user on every street is simply not feasible and a balance needs to be struck.

The word ‘historic’ is redundant, because the age of the streets in the borough is obviously irrelevant; nobody is going to be knocking down buildings of any age to build cycle routes. But ‘narrow’? Really?

Hideously narrow roads, as I’m sure you’ll agree. Yes, unlike the wide open expanses available in central Amsterdam, poor Westminster is desperately short of space.

Hideously narrow roads, as I’m sure you’ll agree. Yes, unlike the wide open expanses available in central Amsterdam, poor Westminster is desperately short of space.

Joking aside, the main streets in Westminster – the places where cycling infrastructure is most needed – are plainly enormously wide. There is no shortage of space, and to talk of ‘balance’ while the width of these streets is used almost entirely for the purpose of funneling motor traffic around the borough is preposterous.

Later in the document we have the priceless

limited road space and competing demands… mean that the ability to physically segregate cyclists on the majority of Westminster’s roads is likely to be limited.

Amsterdammers would wet themselves laughing at ‘limited road space’, but in any case this is disingenuous, as there is no need to segregate cyclists on the majority of Westminster’s streets; they can be separated from motor traffic by means of its reduction and/or removal from side streets, using measures that reduce these streets to access only for motor traffic.

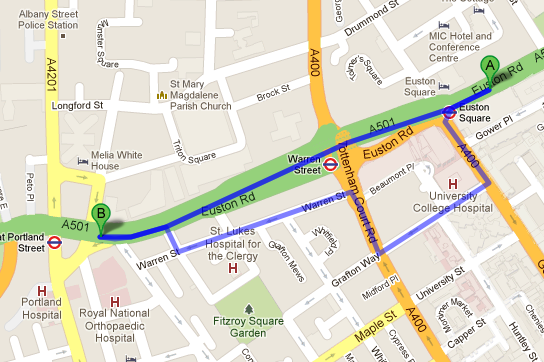

The main roads in Westminster, however, are a completely different story. Included in the Draft Strategy is a map that marks out these roads –

A map that could, theoretically, form the basis for a cycling strategy in a borough that had any serious intent. The red, green and blue roads are almost without exception of ample width, carrying high volumes of motor traffic on multiple lanes (sometimes as many as five or six lanes, as can be seen in the photographs above). Naturally the ‘local access roads’ (in white) should be precisely that – local access only, not shortcuts to somewhere else, and without any need for segregation as a consequence. You wouldn’t even need to tackle parking on these streets.

A map that could, theoretically, form the basis for a cycling strategy in a borough that had any serious intent. The red, green and blue roads are almost without exception of ample width, carrying high volumes of motor traffic on multiple lanes (sometimes as many as five or six lanes, as can be seen in the photographs above). Naturally the ‘local access roads’ (in white) should be precisely that – local access only, not shortcuts to somewhere else, and without any need for segregation as a consequence. You wouldn’t even need to tackle parking on these streets.

Segregation from motor traffic on the coloured roads is eminently achieveable (again, just look at the pictures above!) were it not for those ‘competing demands’, which in Westminster language should be read as nothing more than a desire to maintain the current flows of motor traffic, at all costs.

Indeed, the overwhelming impression from this Draft is that nothing will be done that might inconvenience the act of motoring – any act of motoring – in the borough. The cycling ‘objectives’ are vague and guarded, and hedged with exceptions and conditions. For instance –

The Council will… aim to deliver a range of improved routes for cyclists of different abilities, whilst recognising the needs of other road users and avoiding changes that place unacceptable additional pressure on the road network and kerbside.

That is – not interfering with motoring. Westminster therefore seem keen to ignore completely the main intervention that will enable the uptake of cycling in the borough – separation from motor traffic – and instead employ the spurious, unproven strategy of ‘integration’ with that motor traffic –

There is a need to encourage all road users to show greater consideration for one another and share space in a safe and responsible manner, enabling safer integration and shared routes rather than a presumption for segregation

How will this ‘consideration’ be achieved?

through training programmes, enforcement, education and campaigns targeted at both cyclists and non-cyclists, whilst recognising that many people are now becoming more ‘multi modal’ in their travel characteristics and should [my emphasis] therefore start to demonstrate a greater appreciation of one another’s needs.

Wow. A truly inviting vision of cycling for all – a hopeful reliance on the consideration of drivers as they whizz around you in all directions (and ‘whizz’ they will, because 20mph limits are out of the question, as we will see below).

This reluctance to consider the separation of cyclists from motor traffic on main roads appears to threaten the proposed central London ‘Bike Grid’ outlined in the Mayor’s Vision for Cycling.

Given that Westminster will be at the heart of the proposed Bike Grid, the Council’s participation will be key to the success of the Mayor’s Vision. For Westminster, an important element of this vision is the recognition that physical segregation or the provision of cycle lanes will not always be feasible or expected, particularly where there is significant pressure on footway, carriageway and kerbside space from competing demand.

In other words, Westminster think the flow of motor traffic should trump the comfort and convenience of cycling, even when this directly interferes with proposals contained within the Mayor’s Vision. Westminster can’t even bring themselves to fully endorse pitiful interventions, like feeder lanes and ASLs, that have relatively little or no effect on motor traffic flow –

The needs of cyclists continue to be taken into account in the design of all transport and public realm schemes. Features that benefit cyclists, such as Advanced Stop Lines and feeder lanes, will be integrated where feasible.

And even cheap, easy and painless interventions like a 20mph limit in the borough are rejected by this Draft, on utterly ludicrous grounds –

Whilst the implementation of 20 mph zones falls within the remit of the City Council, this is not something the Council is currently seeking to implement. In terms of cycle safety it is considered that a 20 mph limit could have minimal benefit as traffic speeds in the City of Westminster are often below 20 mph already, with the average speed being just 10mph.

‘We don’t think a 20 mph limit is a good idea, because the motor traffic speeding around our borough occasionally travels at below that speed.’ Hopeless.

With regards to safety, the strategy seems to be ‘encouragement’, training, and expecting road users to ‘look out for each other’ in a way that suggests different mode users bear equal responsibility for danger. The document even suggests ‘cyclists’, as an undifferentiated, monolithic bloc, need to start behaving in order to encourage ‘mutual respect’.

Whilst some accidents may be prevented through improved junction and road design, it must be recognised that accidents are primarily caused by the way that cyclists and other road users interact, and many could be avoided by improved road user conduct and caution…

If cyclists are encouraged to adhere to the rules of the road, hopefully [again, my emphasis] this will also help them to be perceived more positively by other road users and to encourage mutual respect and courtesy.

As someone who is considerate and abides by the rules while cycling on the roads of Westminster, I find it quite offensive that the borough could even imagine that ‘courtesy’ and ‘respect’ towards me is in any way conditional on the behaviour of other people who might be using the same mode of transport. My safety while cycling should be a given, not attenuated because of moronic prejudice. Shame on you Westminster.

Cyclists also need to be aware that pedestrians and motorists will not always be aware of or anticipating their presence, and that they need to play their part in ensuring that they are well seen and heard (for instance through maintaining a prominent position in the road and using a bell to warn pedestrians of their presence.

Miserable, miserable stuff, and needless to say there are no strategies outlined in the document aimed at improving the attitudes and behaviour of private motorists around cyclists, only a ‘hope’ that as more people might cycle, so outright, naked hostility will diminish each group will ‘have a greater appreciation of each other’s behaviour and frustrations’. Bless.

A big long list of piecemeal measures follows (including a passage that makes an erroneous connection between red light jumping and deaths as a result of poor visibility from HGV cabs), concluding with

The Council will also run a campaign called ‘Westminster chimes’ giving out free bells to cyclists, encouraging them to make use of their bell to warn pedestrians of their presence. The Council will also consider a campaign highlighting the dangers of the use of headphones whilst cycling.

Free bells! Such ambition!

It’s a stone-age document. What’s amazing is that some attempts have clearly been made to update it in the light of the publication of the Mayor’s Vision, which suggests it must have been even worse at some point before. There is absolutely no conception of what is required to make cycling an inviting and civilised mode of transport in the borough, even for those who currently cycle through it like me (albeit with some trepidation), let alone the vast majority of people who would not even dare to place their foot on a pedal on Westminster’s roads.

A re-write, please.