After writing recently about gryatories and one-way systems – and how they can actually be beneficial for cycling, if applied judiciously – I thought I’d turn my attention to another piece of much-maligned urban infrastructure, the humble bollard.

Frequently impugned as an ugly feature of the urban environment – ‘bollardism’ – bollards, applied properly, are a cheap and easy way of civilising streets; indeed a simple way to turn a ‘road’ in to a ‘street’.

There are several new examples in London. Stonecutter Street has recently been closed off to motor vehicles (but remains permeable to bicycles and pedestrians) at the junction with Blackfriars Road.

Likewise Earlham Street has been closed off at the junction with Shaftesbury Avenue, turning a nasty rat-run into a civilised street with people happy to mingle in the road (no particular need for any re-paving here).

Likewise Earlham Street has been closed off at the junction with Shaftesbury Avenue, turning a nasty rat-run into a civilised street with people happy to mingle in the road (no particular need for any re-paving here).

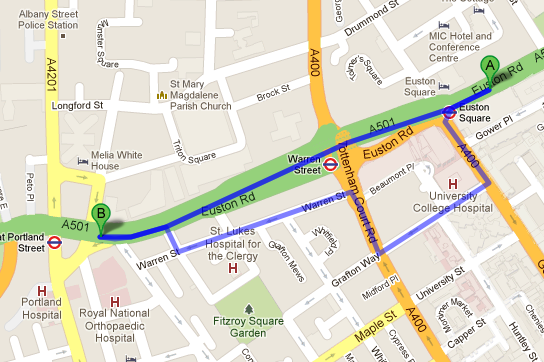

And (in Camden again) Warren Street has been closed off halfway down.

And (in Camden again) Warren Street has been closed off halfway down.

In all of these cases, the intention is to force motor vehicles to use the appropriate adjacent road, instead of cutting through. Motor traffic should be using Euston Road, instead of Warren Street, for instance.

In all of these cases, the intention is to force motor vehicles to use the appropriate adjacent road, instead of cutting through. Motor traffic should be using Euston Road, instead of Warren Street, for instance.

And it should be progressing down Shaftesbury Avenue, instead of Earlham Street.

And it should be progressing down Shaftesbury Avenue, instead of Earlham Street.

Likewise, Stonecutter Street is designated as a ‘Local Access Road’ in City of London documents, and it is now being treated appropriately by being closed off; it is now genuinely only an ‘access road’, rather than a shortcut to somewhere else.

Likewise, Stonecutter Street is designated as a ‘Local Access Road’ in City of London documents, and it is now being treated appropriately by being closed off; it is now genuinely only an ‘access road’, rather than a shortcut to somewhere else.

Of course, a legitimate concern that is expressed is that these kind of arrangements simply displace motor traffic onto other roads and streets; that a problem is simply pushed elsewhere.

There are two ways of responding to this; the first is to point out that some roads are much more suitable for carrying motor traffic than others. Euston Road is the right place for motor traffic, and it doesn’t make any sense to dilute the amount of motor traffic on it by allowing some of it to progress down Warren Street.

Secondly, in closing out motor traffic from these ‘side’ streets, we shouldn’t abandon the main roads, and simply allow them to become dominated by motor traffic. Main roads should also be civilised places. Applying filtered permeability to side streets should only be a part of a comprehensive network strategy, one that sees main roads with appropriate treatments for walking, cycling and public transport. If main roads are comfortable and attractive places to cycle, for instance – with the addition of cycle tracks – then that ‘displaced’ motor traffic can and should evaporate entirely.

By way of example, it’s worth pointing out that ‘main roads’ in Dutch towns carry considerably less motor traffic than the equivalent urban roads in Britain, despite a policy of making side streets virtually impossible to use by motor traffic attempting to pass through. There is no ‘displacement’, because the entire urban environment is conducive to cycling, and so any excess motor traffic that might have been forced onto main roads simply doesn’t exist. That ‘traffic’ is on bicycles instead.

Indeed, when I present pictures of ‘main roads’ in Dutch towns and cities with cycle tracks, I am often met with comments that suggest the road is ‘quiet enough’ not to justify cycle tracks at all. There are many examples in the city of Assen, where ‘main roads’, with cycle tracks, appeared (to me at least) to carry far less motor traffic than an equivalent UK road, despite the side roads being closed off. And this is because people are travelling on bikes instead, to a large degree. This picture of a main road was taken at about 5pm –

The road here (a main route into the centre of town) was significantly less busy with motor traffic than a similar road in the UK.

The road here (a main route into the centre of town) was significantly less busy with motor traffic than a similar road in the UK.

Here are some more ‘main roads’, this time in Amsterdam. These are the only available routes to motor traffic, but are nowhere near as congested or dangerous as urban main roads in Britain, despite the smaller network available to that motor traffic.

The point is that motor traffic won’t be pushed onto these roads if you have a coherent policy of making cycling an attractive alternative to driving in urban areas; much of the motor traffic will cease to exist.

In Utrecht ‘main roads’ are even being removed completely, despite limited permeability elsewhere on the network for motor vehicles, because they’re not needed anymore.

An urban motorway in Utrecht in 2011, which is currently being removed and replaced by the canal that originally existed here, a bus route, and cycle tracks

A policy of ‘bollarding’ won’t necessarily result in displacement of motor traffic if a sensible strategy of enabling that traffic to shift to other modes is in place.

More bollards please!

Great post – I love that Utrecht are taking out former main roads.

Outside London and maybe in outer London, I can see the reduction in car trips happening as you describe, but in inner & central London now the vast, vast majority of traffic (in my experience) is buses, taxis, and service vehicles (delivery trucks, trade white vans, etc). Only the most ardent of motorists are still driving private cars out of choice in those central areas, and you may get some of those converted to bikes but likely not a significant number.

I suppose another way of looking at it (that would support the traffic evaporation concept) is that stopping taxis rat running would, over time, make taxis less attractive as a transport option so we may see a reduction in those – particularly with cycle hire providing a good alternative to black cabs for many central London journeys. £2 cycle hire plus a 10 minute cycle vs £15 taxi taking 20 minutes makes the bike option highly attractive.

Apologies for the rambling comment!

Super! After they are in (or as encouragement to get community support for them) why not have the whole community get involved in decorating them like we’ve done here in Whitchurch, Hampshire? See http://WhitchurchBollards.org.uk

In many ways, bollarding is even more preferable to separated cycle lanes. It is less expensive for Councils etc to install, less intrusive in the general street scape, and streets broken by bollards are still accessable to cars but just not as alternative routes through. Lets have many more bollards.

While I think Mark Hughes is broadly right to say that other vehicles make up the vast majority of traffic in Central London – purely private passenger cars, excluding taxis, minicabs, small hatchbacks being used as vans by IT engineers and office equipment service personnel etc, are relatively rare – it actually doesn’t take much of a reduction in volumes to make a marked difference in congestion, to everyone’s benefit. Look at what happens in school holidays for example, when by some estimates up to 20% of cars (not all traffic) on the roads at certain times are school-run traffic. Or what happened in London during the Olympics. Despite the reduction in capacity due to the ORN, there was if anything an improvement in general congestion. “Traffic Evaporation”, as described in academic studies, was visible for real. I am not aware that the world came to a standstill.

On another point, you note that there is a lot less traffic on Dutch through roads, even though access roads are rendered impermeable and so can’t be used as rat-runs as so many of our city streets can. I guess this must be entirely due to the transfer of short journeys from car to bike or public transport. Here, we are told that in a big city more than half of all car journeys are less than 5km and about a quarter are less than 2km – I think similar numbers apply to non-urban areas if you substitute mile for kilometre. Only 2% (at best) of UK trips are by bicycle, so if that became 20% or as in the Netherlands close to 40% it is hardly surprising if the roads are clearer – even if the total car mileage is not greatly reduced because of the weighting effect of longer trips, the impact of local traffic is perhaps disproportionate.

And the fewer cars on Dutch roads doesn’t mean that the have fewer cars. According to this http://www.nationmaster.com/graph/tra_car-transportation-cars with info sourced from the World Bank, the car ownership per 1,000 population in the Netherlands is actually slightly higher (and Denmark is only slightly lower) than the UK. It is not car ownership which is different, but car use. Other stats from the EU (I can’t find the link now but I think I put it on the CEoGB database) suggest that the Dutch and the Danes, using their cars less frequently, keep them longer than we do, with the average age of the UK, Dutch and Danish car fleets being, as I recall, something like 5.9, 7 and 8 years respectively. Not because we are richer and can afford to change more often, but because theirs wear out less quickly.

If that means that the only casualty of traffic evaporation would be the motor manufacturers, I am not going to cry over that – the industry has only managed to survive at all through massive taxpayer subsidy, whether visible or concealed, over the last century and I for one am tired of seeing my tax bill poured down that particular toilet.

Another reason for Danes and Dutch people keeping their car for longer is the higher taxes on new cars. A quick look at Ford’s UK, Dutch and Danish website reveals that the cheapest Ford Focus (regardless of comparable equipment, just the cheapest listed on their websites) in each country cost £13,995 in UK, £16,455 (€19525) in the Netherlands and £22,580 (199,990 DKK) in Denmark.

I am new to this website and I must say it’s a pleasure to read relevant, serious and concise comment such as the above. Thank you, I shall keep dipping in.

Pingback: Subversive Suburbanite