The best of the new cycling infrastructure in London is almost entirely composed of bi-directional cycleways, placed on one side of the road. This includes pretty much the entirety of CS3 and CS6 – the former running from Parliament Square to Tower Hill, the latter from Elephant and Castle to just north of Ludgate Circus.

Bi-directional cycleways are often not the best design solution, but the decision to go with bi-directional cycleways is not an accident. Undoubtedly people at Transport for London have thought long and hard about the best way to implement cycling infrastructure given current UK constraints, and have plumped for two-way as the most sensible approach.

To be clear, bi-directional cycleways do have serious downsides – they can lead to more conflict at side roads as cycles will be coming from unexpected directions, and pedestrians in particular may find them harder to deal with. Head-on collisions with other people cycling are also more likely. On ‘conventional’ streets – one lane of motor traffic in each direction – uni-directional cycleways are clearly preferable, all other things being equal.

However, bi-directional cycleways do also have advantages, and one in particular that has probably swayed the decision-makers in London. It’s touched upon in this excellent summary of the advantages and disadvantages of bi-directional and uni-directional approaches by Paul James –

Depending on the roadway in question you could have less junctions to deal with, if you have many turnings on one side of the road, running a bi-directional cycleway on the opposite side so as to save on conflicts might be a good idea.

This is clearly the reasoning behind putting a bi-directional cycleway on the ‘river’ side of the Embankment. There are no junctions to deal with, cycling in either direction, so even though people are cycling on the ‘wrong’ side of the road, heading east, that’s a lot safer (and also more convenient) than having to deal with all the side roads that do exist on the non-river side of the road.

Cycling on the ‘wrong’ side of the road, heading east. But no side roads to deal with, so safer, and more convenient.

But this isn’t the only type of conflict-avoidance that explains why bi-directional cycleways have been chosen in London. Bi-directional cycleways also reduce conflicts at junctions that have to be signalised, by ‘bundling up’ all the cycle flows on one side of the road. This is actually very important, thanks to the limitations of current UK rules, and it’s the subject of this post.

In all the countries in mainland Europe (and also in Canada and the United States) it is an accepted principle that motor traffic turning right (the equivalent of our left) with a green signal should yield to pedestrians (and people cycling) progressing ahead, also with a green signal. Here’s a typical example in Paris; the driver is turning off the main road, with a green signal, but pedestrians also have a green signal to cross at the same time. The driver should yield (and is).

Two ‘conflicting’ greens, circled

This approach actually makes junctions very straightforward, and efficient. A complete cycle of the traffic lights at a conventional crossroads requires only two stages to handle all the movements of people walking, cycling and driving. In the first, walking, cycling and driving all proceed north-south (with all ‘turning’ movements yielding to ‘straight on’ movements), and in the second, the same, but in the east-west direction.

Motor vehicles, red arrows; cycling, blue; pedestrians, green

Compare that with a typical UK junction, which will have three stages (if it takes account of pedestrians at all) and ignores cycling altogether, lumping it in with motor traffic. First, motor traffic (with cycling included in it) going north-south; then, motor traffic heading east-west; then pedestrians finally get a go on the third stage, with all other movements held.

Motor vehicles in red; pedestrians in green

This arrangement obviously doesn’t allow any turning conflicts (apart, of course, from motor vehicles crossing each other’s paths) – pedestrians don’t get to cross the road until all motor traffic is stopped, with an additional third stage. (This is, effectively, a ‘simultaneous green’ for pedestrians, although we are rarely generous enough to give pedestrians sufficient signal time to cross the junction on the diagonal).

And this gives us a clue to the problem when it comes to adding in cycling, when these kinds of turning conflicts aren’t allowed. You either have to add in stages where motor traffic is prevented from turning, or you have to stop pedestrians from crossing the road while cyclists are moving. Both of these approaches would add in a large amount of signal time, and would make for inefficient junctions.

One possible answer is including cycling in the ‘simultaneous green’ stage, but with sensible design – cycles moving from all arms of the junction at the same time as pedestrians have their green, and pedestrians crossing cycleways on zebra crossings. For whatever reason (from what I hear, DfT resistance) this kind of junction is still not appearing in the UK, forcing highway engineers to improvise within the constraints of the current rules. As Transport for London have done.

If we are trying to build uni-directional cycleways, those UK rules effectively mean we either have to ban turns for motor traffic, or we have to employ very large junctions indeed, to handle signalising different movements. Take the Cambridge Heath junction on Superhighway 2, which has to use three queuing lanes for motor traffic in each direction. One for the left turns (which have to be held while cyclists and motor traffic progress ahead), one for straight ahead, and one for right turns (which have to be separate from straight ahead movements, otherwise the junction will clog up).

That’s an awful lot of space when you add in the cycling infrastructure – space not many junctions in urban areas will have.

In an ideal world – and with sensible priority rules – these junctions could just be shrunk down to two queuing lanes in each direction. A left turning lane combined with a straight ahead lane, and a right turn lane. All these lanes would run at the same time as cycle traffic progressing ahead (as well as pedestrians), with the left turners yielding.

Unsurprisingly this is – of course – how the Dutch arrange this kind of junction.

A typical Dutch junction with separated cycling infrastructure (flipped for clarity). Motor traffic from this arm will have a green in all directions at the same time as cycling running in parallel.

This is much more compact than the kind of ‘Cambridge Heath’-style junction that we are forced to employ in Britain.

But, given that we unfortunately can’t do this, and that we rarely have the kind of space available that there is on Superhighway 2, bi-directional cycleways are the most obvious answer. As I hinted at in the introduction, this is why they’ve been used by Transport for London – they’re not stupid!

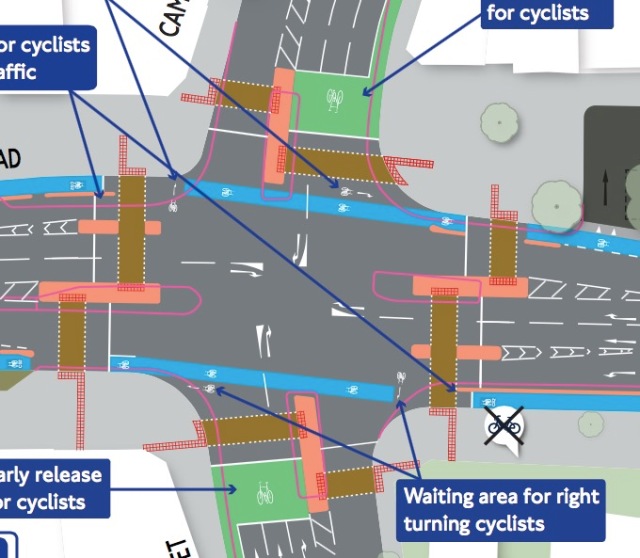

Let’s take one of the junctions on the North-South superhighway, at Ludgate Circus. Space here is much more limited than on CS2 – we can’t add in multiple turning lanes – so that means, given the constraints of UK rules, a bi-directional cycleway is the most sensible option.

‘Ahead’ movements running in parallel with ‘ahead’ movements for cycling. (Arranged with North at the top).

Only two queuing lanes for motor traffic are required, in each direction, making this arrangement much more compact. It helps, of course, that a bi-directional cycleway is more space-efficient than two uni-directional ones, but the main win here is the fact that all the potential conflicts are ‘bundled’ on one side of the road. That means motor traffic flowing south doesn’t have turning conflicts on the inside.

Clearly, as I’ve outlined early on in this post, bi-directional cycleways will, more often than not, be less desirable than uni-directional ones, in urban areas. But they are currently – thanks to UK rules – probably the best way of building inclusive cycling infrastructure when space is genuinely limited, as they are the simplest way of side-stepping around British priority rules. (An additional benefit is that they will typically only involve converting, at most, a single lane of motor traffic, which helps when it comes to persuading reluctant local authorities worried about retaining capacity for drivers.)

Perhaps the way forward is to continue building bi-directional cycleways, but keeping in mind the possibility of adapting bi-directional designs into uni-directional ones, if and when UK rules become more flexible, or if and when ‘simultaneous green’ arrangements start to appear.

Another attraction of two-way cycle tracks is that deliveries ,essential parking etc can take place on the other side of the road. Yes, I know you could put it outside of the cycle track but planners will never put in a wide enough separator to keep doors from being opened into the face of cyclists.

Also, the bi-directional path has a great advantage for people with their origin and destination on that side of the road, since it avoids two crossings.

For those reasons, on busy roads, you often see a bidirectional path on both(!) sides of the road in the Netherlands. That’s definitely the best of both worlds.

Another advantage is for heavily-peaked unidirectional flows, the bidirectional lanes can support a larger number of cyclists moving in the same direction as people will spillover into the available space.

Of course that is a bit rough for people going against the flow. But this usually sorts itself out. And in the long run, the bidirectional lane can become a unidirectional lane when a second unidirectional lane is added on the other side of the street (like done recently with some old crap infra).

Hi Mark, I don’t agree that it is a good idea for motorists to be given a green at the same time as pedestrians, meaning turning traffic yields to pedestrians, as there can be conflict. I have seen that and experienced it a bit in the USA. David Hembrow believes, as do I, that if you have a green you may go (except for simultaneous green for cyclists, in which case one could have a give way to left or right rule). He claims that nearly always in Assen and Groningen green means go, and it is very rare that turning cars must yield to pedestrians because of the signal timings. I am impressed with your explanations and research though. Thanks as always

There can be many nuances with the phasing of signals. In Australia the simultaneous greens for pedestrians and vehicles are released at the same time, so the vehicles are moving from stopped. Pedestrians who arrive at a green light for traffic have to press the button and wait an entire cycle and for all directions to stop before they will be given a new green light.

All very good points. The turning traffic gives way to pedestrians principle goes beyond Europe and North America. I believe it applies in every single country except the UK, Ireland and Hong Kong, where there has obviously been a strong British influence. Even Australia allows pedestrians to go with parallel traffic! While UK visitors in other countries often find it off-putting at first to see cars turning across crossings showing a green man, I think you start to realise the advantages when you see that you get exponentially more green man time (as long as the junction is not too big). In the UK you may get 6 seconds of green man time in a 90 second cycle, but in Germany you might get 35 seconds! Unless pedestrian flows are high, I think it’s also more efficient for cycle and motor traffic.

Vehicles turning across oncoming traffic also have to give way to pedestrians. This gives drivers more to think about, but it obviously works well enough in other countries.

Implementing this in the UK would be possible, but difficult. I think the public would need to be informed of the changes beforehand, clear, distinct markings would be needed (perhaps yellow stripes) and clear flashing amber lights would be needed (like is used in some European countries). There would probably be a temporary increase in pedestrian injuries, so this would need careful attention.

It is not so simple as saying that everywhere allows this. New York City for example has banned right turn on red completely. Based on the behaviour I see from drivers on a regular basis I am very dubious about how well they will behave. I can see a lot of reruns of the always great to hear “well you might technically be in the right, but that won’t help you when you are under a car because you assumed they would yield”.

There’s a good chance that pedestrians and cyclists, unless they are in a critical mass, will lose a significant amount of priority at signalised junctions where they have a green light. These effectively being transformed in to misleading pelican crossings where in theory you can just cross, but in reality you have to put your foot out and see if the cars are actually going to yield. Then hope that someone doesn’t come barreling around the corner on their phone while you are crossing.

Another issue are the junctions where the turns are curved to allow motorists to maintain speed while turning. This is fine when they have a green light but if someone is approaching at 50kph and preparing to take the turn I would have zero confidence that they would slow down enough to notice a pedestrian or cyclist crossing.

I strongly suspect that enough drivers will hear “you can turn left on a red” and not listen to the rest to make crossing the road far more dangerous.

It is worth pointing out that at non-signalised junctions motorists are already supposed to yield to cyclists that want to go straight ahead but they frequently do not. A friend of mine was told by an angry motorist that the rules of the road were that cyclists always yield to motorists. They introduced a dutch style roundabout near me with yield signs on the road to show that motorists must yield to cyclists traversing the roundabout in the segregated lane on the outside. Predictably in my opinion motorists found the yield signs confusing and assumed that cyclists must yield to them and after recording a large number of near misses this experiment was abandoned in favour of returning to the norm where cyclists were part of the traffic flow.

I think right on red is a separate issue with its own problems and advantages. I haven’t yet been anywhere where right on red is widespread, so I can’t really comment on it. We’re talking about traffic going parallel to pedestrians and cyclists having a green light at the same time.

Cyclists have priority over turning traffic when they’re in a cycle lane. If there’s no cycle lane, then the Highway Code doesn’t mention priority for cyclists.

Where’s this roundabout that had priority for cyclists?

That would be the Killiney Towers roundabout in Dublin. You can see a video here:-

I overstated/misremembered how “Dutch” this was. Basically there is a cycle path around the perimeter of the roundabout. Cyclists used to be legally required to use this. Anyone familiar with roundabouts is aware that positioning yourself on the outside rim of the roundabout is asking to get hit by exiting cars who assume (primarily because it is convenient for them) that you are exiting too. You can also get hit or be forced to brake by entering cars who also assume (for the same reason) that you are exiting so they can enter.

Painting huge YIELD TO CYCLISTS signs on the road didn’t help. There were a number of near misses recorded. Motorists claimed that the yield instructions were confusing or that they assumed it meant that cyclists should yield to cars (presumably because well of course they should).

I disagree that having only two signal phases at urban junctions is unilaterally more efficient than allowing for a #pedestrian only “scramble phase” as, you state, is the norm in the #UK. In terms of efficiency, two-phase junctions are only more efficient at moving vehicles when pedestrian flows and turning volumes are low. As pedestrian traffic and turning volumes increase, these junctions become less and less efficient, to the point where large cities like #NYC often resort to banning turning movements at congested junctions altogether.

Although pedestrian scrambles are good where pedestrian flows are high, the problem with the UK system is that it’s inefficient for everyone at probably the majority of signalised junctions. Pedestrians have to wait an age for north-south and east-west traffic while only some cars make turns. Some people give up and chance it, putting themselves at risk of impatient drivers! All traffic also has to stop and wait to let few or often no pedestrians cross. Or worse, no pedestrian crossing phase is provided at all and pedestrians have to guess when cars will go and just step into the road hoping they don’t get run over! This setup is frighteningly common in London.

I also don’t think it’s a bad thing to ban turns instead of providing scrambles. I think banning turns can be better for pedestrians because they get more green time, while scrambles often only give a few seconds of green time to pedestrians in the UK.

Really interesting post. I don’t mind the rules abroad, but can’t see them ever changing in the UK. Far too much risk when people are so used to the current way.

Maybe worth noting that in Seville, the vast majority of cycle infra is bi-directional, even though we have European rules regarding yield on turn. My guess is that it was motivations of minimising impact on traffic (removing one car lane) and getting things done more quickly and cheaply. Doing it (almost) universally this way (with a significant number of kilometres of lanes) means motorists and pedestrians seem to be used to them and it really causes minimal issues. The biggest issue is that some just aren’t wide enough.

I know this blog post isn’t intended as a PR piece for the “conflicting green” concept, but as others have commented on that aspect, I’ll throw in my 2p’s worth too.

Having lived in a country where motor vehicles drivers and people on foot both get a green light at the same time, I have to say I’m not keen on it. I’ve tried to like it, but I just can’t.

Whilst most drivers here do respect the “give way when turning” rule – even at unsignalled junctions – it only takes a small percentage of selfish drivers to ruin the concept for everyone. I’ve seen too many drivers inching their way into crossings as people cross the road, small children scared to cross because of the (very real) threat of a rumbling motor, and seen so many near misses caused by impatient drivers. And if you’re in the road when the lights change – you’d better run!

It also adds an unpleasant dimension to crossing the road. You have a green light, so you begin to cross. Look, there’s a car being driven towards you – will the driver stop at a safe distance? Will they stop halfway into the crossing? Will they try to speed in front of you, or nip behind you? Your only option is to trust that the driver will behave appropriately. It’s uncomfortable enough for us able-bodied young people, I can’t imagine it’s much fun at all for those who can’t move quickly.

I’m not even sure that this “conflicting green” is as efficient as claimed, anyway. For example, there’s a junction near here with a large amount of foot traffic. Most of the time, there is no break in the stream of people crossing the road until the pedestrian signal has gone red, so drivers wanting to turn must wait until the end of the signal phase anyway. From a traffic flow perspective, it’s no better than just giving turning drivers their own phase. It just increases danger to people on foot, for no gain.

So just who does benefit from this system anyway? It seems to me that it’s purely for the priority of motor traffic. There’s no reason why more green time can’t be allocated to people walking and cycling. The only reason to mix people on foot amongst motor vehicles like this, is to cater for large volumes of motor traffic – must keep traffic flowing smoothly!

When we speak of cycling, we speak so often of sustainable safety, designing systems which don’t rely on 100% perfect behaviour. We promote the idea that separating motoring from cycling in either time or space is desirable. We also speak of the importance subjective safety, the lack of which can discourage people from using a mode of transport. I can’t think of a good reason why these concepts shouldn’t be applied to walking too, and this “conflicting green” concept ignores all of them.

Ultimately, it’s a tool which is probably over-used, here in Berlin at least. I feel it’s like mixing cycling with motoring – it may be acceptable under certain circumstances, but it’s never actually desirable. And, also like mixing cycling with motoring in the UK, it’s a concept which has been applied with a broad brush, in inappropriate locations, purely for the benefit of people driving.

There is an issue with bi-directional routes whereby people who want to take one of the exits on the other side of the road have a problem. I’ve seen pictures where opposite side turns have exit points in the segregation barrier but I have been on plenty of segregated tracks where cyclists have a problem in this case. In the worst case I want to go 200m down a road and then take a left, but I need to cross this road, use a bi-directional track for 200m then stop and cross the track and then the road like a pedestrian.

This is a case where a properly designed facility will work well but a badly designed one will make things worse.

Interesting post. Also, interesting timing…

I strongly agree with Schroedinger’s cat. I lived in Berlin for a year, and did not particularly like this setup. It’s a bit intimidating having cars nosing slowly forwards as you cross the road. I really like that in the UK, a green man means really no cars.

The UK does have some of the safest roads in the world, I think. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why. (The other reasons are probably not so good, like the fact that few people cycle…).

It’s my understanding from what Paul James wrote elsewhere. the Dutch try whenever possible not to have turning traffic and cycles having green at the same time. For pedestrians it is not so bad, as they move more slowly and so drivers have more time to see them.

For small junctions, simultaneous green (ideally with two greens per cycle) just seems to me an inherently better way of doing things, and also more easy to fit in with existing UK ways of doing things.

I agree turning cars can be a bit intimidating to pedestrians, although this will vary from person to person of course.

The road safety statistic you’re thinking of is for people in motor vehicles only. Up until very recently, the UK was not as good as many other European countries for pedestrian safety, including Germany. However the UK has made significant improvements and is now slightly safer than Germany for pedestrians, but we’re still nowhere near as good as the Netherlands. When it comes to cycling safety, the UK is not great at all!

Thanks for the correction! I was just thinking of a list of road safety of different countries on wikipedia, not broken down into pedestrians, cyclists, motorists etc.

I think Paul James also has an example from the CROW manual of a small junction without these conflicts, that combines straight on and left turn (in Dutch context) in one lane, and has right turns on the other lane. It would be interesting to know how widely that junction design is used in the Netherlands.

The junction I was thinking of is at the bottom of this page:

“I really like that in the UK, a green man means really no cars. ”

except when you’ve got some toerag who has seen the amber as a challenge and he is going too fast to stop like the one who almost took me out yesterday when I was about to ride across a Toucan with my ‘green bike’ showing. Something made me hesitate…

“I really like that in the UK, a green man means really no cars.”

Don’t disagree with the general thrust of your point, but there are disadvantages to this too: the other one being that cars assume green means green as well. I happened to be in a police station when a woman who walked with a stick came in to report an incident. She had started to cross the road on green, but because she walked slowly, she was still walking when the lights changed again. A driver drove straight into her: looking at the lights rather than the road.

I experienced the give way when turning on green system for many years in Poland and it actually works well there, which is surprising as drivers have little respect for pedestrians on zebras or during the right turn on red (which is of course a separate system that just happens to also be used there). But that doesn’t mean it’s bound to work well elsewhere – traffic is highly cultural.

What would be allowed in the UK for left turns if 2 cycleways intersected at a signalised junction?

https://goo.gl/maps/TwLuYL8MvKo

I think HivemindX makes (if I understand him/her correctly) a good point.

What happens if you want to left at a junction when the bi-directional track is on the right of the road? E.g. in your example above, going south you want to turn up Ludgate Hill? Or on the same route further south, what do you do if you want to go east when travelling south down the CSH at Southwark Street? It seems to me that you are being inconvenienced more than before the infrastructure went in, and that you wouldn’t have that problem with 2 uni-directionals. There is the advantage that you can have fewer junctions with bi-directional, but the inconvenience I mention seems real. Within the existing legal structures how would you address this problem?

rdrf, this is the issue I was raising exactly. Although this is a problem for unidirectional segregated cycle lane as well

I’ve been on, one way, cycle tracks which have a raised kerb separating me from the road, which caused me a problem when I wanted to turn right on to a side street.

I thought I had seen in this article, but it must have been elsewhere, example of two direction cycle tracks where an exit on the opposite side of the road means a break in whatever is being used to provide segregation too. This means when you want to take a side street on the far side of the road you can pull in to the gap in the segregation barrier and either wait to cross or merge across immediately if traffic flow allows that.

I don’t think this is quite as good as being on the road itself and being able to merge in to the right turn lane (as an example) when the opportunity arises but it is a good compromise which gives you the benefits of segregation and convenience during straight ahead travel but doesn’t inconvenience you overlay when you need to leave. It’s a lot better than providing nothing and requiring cyclists wishing to make a turn dismount and cross as a pedestrian, assuming that is even legal.

Bi directional paths always have the problem that they are significantly less convenient than simply using the road for someone who wants to enter the road and leave it relatively soon both from and to the other side from the cycle path.

Especially where tidal flow exists, bi-directional provides far more width – it allows for cyclists to ride side by side and still have someone overtake. The benefit of this can’t be overstated. Occasionally this has been attempted more formally with motorised traffic – central lanes which change direction – but I’ve never seen it work well. Since cycling is less formal wrt lanes there are advantages. The width also makes for a more pleasant experience, on a surface that feels nice and expansive without kerb hazards. It’s easier to appreciate the space provided for cycling when you see it all in one place.

I have argued the case for bi-directional lanes previously (and seen the writer argue against; that they are bad infrastructure). I’m pleased to see people coming around to the idea that every route is different. It depends very much on the context.

HivemindX said: “Bi directional paths always have the problem that they are significantly less convenient than simply using the road for someone who wants to enter the road and leave it relatively soon both from and to the other side from the cycle path.”

That’s my point entirely. If any Londoners have any ideas about how to engineer/re-phase signals for the turn left into Southwark Street from the cycle track on the right hand side going down (southwards) over Blackfriars Bridge, it would be nice to see it.

I agree with most of it but I’m disappointed by the repetition of the myth: “bi-directional cycleways do have serious downsides – they can lead to more conflict at side roads as cycles will be coming from unexpected directions”

The conflict already exists because motorists seldom expect cyclists to be anywhere near any carriageway. Bidi tracks just move the conflicts around: it can be to more difficult locations (on the apex of the turn) or safer ones,depending on how good the designer is.

Being dutch, I have my doubts on that statement. In the Netherlands, motorists do expect cyclists. But bi-directional paths are an exception, and chances of being overlooked or ignored when cycling from the wrong direction are, in my experience, much higher on those.

Are they really an exception? I spent days cycling around Holland and Utrecht earlier this year and the only unidirectional paths I remember were in Katwijk, Lisse and Aalsmeer. Unidirectional paths seemed like an urban exception to the bidi rule.

But really my statement was directed at England. Dutch motorists in general seemed to expect cyclists more. I’ve cycled in several countries and the only place so far I’ve ridden which rivals England for motorists seeming surprised that there are other types of road user is Florida.

You;re right, of course, outside of the cities, most bikes paths are bidirectional. I was talking about the urban case, where most of the cycling is done.

Motorists in England are a strange breed. I haven’t cycled much there, but as a pedestrian, i’m often confused. E.g. highway code 19 (as a pedestrian, cars should stop for you when you’ve started to cross on a zebra) seems to be reasonably safe to rely on, but 170 (cars should stop if you’ve started to cross a side street where they’re turning into) seems completely random or a long-forgotten rule? If you can’t rely on reasonable behaviour in common encounters between pedestrians and motorists, i wouldn’t expect it in the rare cases they’ll encounter a cyclist.

You’re right that zebra crossings are reasonably well respected, and of course it’s the law that vehicles must stop when someone is on a zebra crossing.

Rule 170 may as well not exist! It’s not an enforceable law, and most people don’t know about it. I don’t think it’s taught as part of driver training. At most it may be mentioned casually a couple of times during driving lessons. If you’re assertive, most drivers will wait when turning (because you give them no choice!) but the second you hesitate when crossing a side road, they’ll turn in front of you, because that’s the normal, expected behaviour here.

When I was walking with a group in Geneva once, I was very, very confused when a van driver who wanted to turn right in front of us stopped and waited, and outright refused to turn before us. Now I get it, but I had no idea at the time why he was doing that!

Exactly. In the Netherlands, the German-speaking countries, and quite likely on most places on the mainland (I’ve never given it any thought, except in Britain), that rule is just normal behaviour. Every road user continuing on the same road that you’re trying to leave has priority. But it’s the implementation of that same rule that allows cyclists to safely use the road. Without ‘rule 170’, cars aren’t forced to watch for anything next to them when turning. Whether that’s the very common pedestrian, or a rare cyclist, doesn’t make much of a difference.

You’re right that drivers don’t expect anything on their left side when turning, and they don’t normally look. Like it was explained in this blog post, even at traffic lights, drivers don’t think about pedestrians when turning because pedestrians are on a red man, unlike everywhere else in the world. This further reinforces the idea that you don’t need to look for anything when turning left. This creates a bit of a headache when trying to build cycle tracks with priority over turning traffic – British drivers just don’t know what to do!

Is it really true that most of the cycling in the Netherlands is urban (where uni-directional seems common) rather than suburban and rural (where bidi seems the norm)?

Even where there were tracks on both sides, riding contraflow seemed fairly widespread (including me at least once)… and the nearest miss I’ve had this year was while I was riding with-flow – a dopey motorist pulled out across the track through a gap in cycles that would have only just been long enough but the carriageway wasn’t clear, so he stopped and caused several cyclists to do emergency stops.

What makes Rule 170 unenforced while Rule 17 is adhered to is a difference in law. There is actually nothing to enforce in the case of Rule 170. The Highway Code is not law in itself, it’s a guide. Rule 17 represents a law about behaviour at zebra crossings, while 170 is just advice. It might be possible to construe it as driving without due care or similar, but that would require police and CPS to interpret it that way (and there are problems with the wording of “due care” laws too).

The other thing is, of course, that Rule 170 is mostly unknown.

While we’re on the subject of pedestrians…Am I the only person in the UK who gets infuriated that almost without exception no pedestrian appears to have heard of HC Rule 2? “If there is no pavement, keep to the right-hand side of the road so that you can see oncoming traffic.” One would have thought basic common sense would have taught anyone that facing oncoming traffic is a whole lot more relaxing than having to glance back anxiously every few seconds to make sure you are not about to be mown down from behind!

Pingback: Rita Krishna: London’s new cycling infrastructure makes things worse for pedestrians – On London

Submitted as comment on originating ‘blog for moderation 2018-09-01 12:07 ↓

Seems more likely a ‘belief’ that bidirectional cycleways require less highway land than two unidirectional ones. A good argument for getting rid of nearly half of [bidirectional & redundant paired] UK (incl. London) footways, too. Presumably, the author is content for the ‘experiment’ with a majority of bidirectional ‘main’ carriageways to continue yet awhile?

As there are such a tiny number of bidirectional cycleways in London, ‘it seems probable’ that it may not be possible to draw any statistically significant conclusions from them. Shame!

Pingback: Are Bi-Directional and Center Bike Lanes UNsafe? – Transit Ninja's Treehouse

The problem with the ahead and left and the right turn lane is that when the left turn is yielding to pedestrians you vehicles trying to then go around them. In Australia the yielding car turns towards the ped crossing and blocks off any cyclist route.

They usually introduce another lane so ahead traffic does not get blocked and the loser here is usually the cycle lane which gets cut before the intersection.

We are starting to see more cycle lanes go all the way to the intersection but cyclists still get blocked by angled traffic giving way to peds. Add to this, the road rules say you should cannot undertake a car that is indicating and turning.

It gets very messy unless there is dedicated cycling infrastructure that continues through the intersection.

Ni Site! It gets very messy unless there is dedicated cycling infrastructure that continues through the intersection.