The Hierarchy of Provision – the official approach to improving roads and streets with the aim of enabling and encouraging cycling – has come in for a fair bit of stick recently, from a variety of sources, including this blog.

One of the main issues, if not the issue, we all seem to have with the Hierarchy is its lack of clarity about the appropriate treatment for a particular road or street. It suggests attempting to apply a series of different measures, in order of importance, to streets, apparently regardless of the function of those streets.

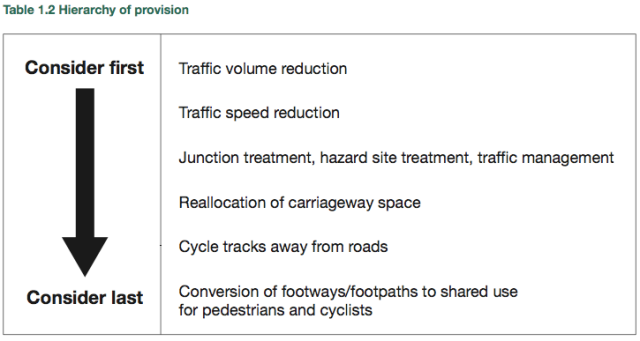

This is the Hierarchy as it appears in the Department for Transport’s Cycle Infrastructure Design [pdf], LTN 2/08 –

And this is how it appears again in the DfT guidance published last month, Shared Use Routes for Pedestrians and Cyclists [pdf], LTN 1/12 (note that it has been slightly modified) –

The changes amount to an insertion of ‘HGV reduction’, and the replacement of ‘cycle tracks’ with ‘shared use’ (it should be stressed, as I pointed out in this earlier post, that this DfT document isn’t very clear about what ‘shared use’ actually means).

Finally, the CTC version of the Hierarchy of Provision included in their new briefing note, Cycle-friendly design and planning [pdf], is different again, and is, in my opinion, the worst of the three versions –

The reason it is the worst is because it advises ‘conversion of footways’ if space cannot be reallocated from the carriageway. It does not countenance the construction of cycle tracks, away from the road, if carriageway space is not reclaimed.

Personally, I believe high-quality cycle tracks should be created regardless of whether motor traffic is, or can be, reduced, if space is available. But the CTC have seemingly sacrificed good quality provision on the altar of reducing motor traffic; the type of provision seen in the photograph below would not be considered under the Hierarchy seen in the CTC briefing note.

Amsterdam. Carriageway space has not been reclaimed, nor has motor traffic has not been reduced on this road. But the footway has not been converted to ‘shared use’; a cycle track has been built away from the road.

The CTC had this to say just the other day, in response to a call for them to demand high quality segregated provision, instead of plumping for second best –

The danger with: “[d]emand the best, and who knows, we may even get what we want one day” is that it is exactly right – we don’t know, and we may not get what we want. We may get ersatz segregation, which could be far worse.

I think this comment is, frankly, a bit rich when you consider that “ersatz segregation”, in the form of the conversion of footways, is actually endorsed by their very own hierarchy, in situations where carriageway space is not reallocated.

Consider, hypothetically, that TfL won’t reallocate carriageway space or consider the reduction of traffic speed or volume on a particularly busy London road. Perhaps on the A24 in Merton, which is currently open to consultation –

We run our fingers down the CTC’s hierarchy, finding out, to our slight surprise, that we have to resort to converting this footway to shared use; the very kind of “ersatz segregation” the CTC present as a bogeyman, a reason why asking for segregation of any kind is potentially dangerous.

To me it is rather odd that ‘conversion of footways’ is even included as an option at all, especially by an organisation so wary of the perils of poor off-carriageway provision; the principle of ‘footway conversion’ lies behind nearly all the terrible ‘infrastructure’ that has made the UK something of a joke when it comes to cycling provision.

Another issue arises when we consider the application of the Hierarchy to roads like these –

That is, semi-rural roads, with little motor traffic (at least by UK standards) and speed limits of 30 to 40 mph. The Hierarchy would maintain that ‘cycle tracks’ (or, worse, ‘shared use footways’) would be the last resort here, and might not even be necessary given the low traffic volume. This is a stance that Chris Juden of the CTC has argued the Dutch take too –

Separate sidepaths are a last resort for the Dutch too. They are provided where the road simply must carry significant traffic at a much higher than cycling speed.

But this doesn’t make any sense, because there are many, many roads and streets in the Netherlands where motor traffic volume is very low indeed, and that have low speed limits, yet cycle tracks are still provided alongside them, for the ease, convenience and comfort of cyclists. This is because Dutch design starts from the principle of keeping cyclists away from motor vehicles, as much as is possible. The Hierarchy, on the other hand, starts from the principle of trying to keep motor vehicles and cyclists together, as much as is possible, which is obviously very different. (David Arditti has provided a long and detailed rebuttal of the misunderstandings of Dutch policy contained in the rest of that comment by Chris Juden).

Furthermore, DfT guidance actually advises abandoning the Hierarchy in just these kinds of situations –

if scheme objectives suggest a clear preference for providing cyclists with an off-carriageway facility, as might often be the case in rural settings, creating a shared use route might be highly desirable… Such routes can be particularly valuable where a considerable proportion of cycle traffic is for recreation, and they could be of particular benefit to children and less confident cyclists. In this situation, on-carriageway provision could be last in the hierarchy.

In other words, if you are concerned about providing for children, consider first what the Hierarchy recommends last.

Another ‘Dutch’ defence of the Hierarchy of Provision involves presenting it as a way of achieving Dutch infrastructure. One of these was on Twitter from Adrian Lord –

how can you create dutch infrastructure without HoP? Demolishing buildings instead?

The clear implication being that the Hierarchy of Provision is necessary for the creation of Dutch-style infrastructure; that cycle tracks can only be created once we have applied the measures of the Hierarchy, namely ‘traffic reduction’. If we don’t reduce traffic, we can’t fit in the cycle tracks without ‘demolishing buildings’.

For a start this ignores the fact that cycle tracks can be (and are!) built alongside roads and streets without any reduction in motor traffic. Indeed, cycle tracks are presented by the Hierarchy as the solution when you can’t reduce motor traffic volume, or speed. As, typically, these kinds of roads are already very large and wide, ‘demolishing buildings’ is obviously not necessary.

So on the one hand we are told to use the principles of the Hierarchy to reduce motor traffic volume so we can build cycle tracks; on the other hand, we are told, by the principles of the Hierarchy, to build cycle tracks when we can’t reduce motor traffic volume.

This strikes me as a recipe for complete confusion when we come to consider a busy road, because on the one hand we have some advocates of Hierarchy saying that we can only build cycle tracks if we reallocate carriageway space, having already reduced motor traffic, and, conversely, the Hierarchy itself saying that cycle tracks are appropriate where motor traffic cannot be reduced. Which is it?

Another example. A similar kind of point to that made by Adrian Lord was presented in a series of tweets from Mark Strong –

As a local I can tell you that [Old Shoreham Road in Brighton] actually is good example of hierarchy of provision.

It was only possible due to Brighton bypass leading to traffic reduction on old A27.

Plus more recent decisions to reduce A270 speed limits to 30 from 40.

This is same basis that has allowed #lewesrd scheme to go ahead (not that I wanted bypass)

Again, a claim is made that it was a policy of following the Hierarchy of Provision that enabled the cycle tracks to be built. In this case, Measure 1 (traffic volume reduction) was achieved by the construction of the A27 bypass around Brighton and Hove (which runs parallel to the A270, the Old Shoreham Road), and Measure 2 (traffic speed reduction) was achieved by lowering the speed limit on the A270, from 40 mph to 30 mph. Once these measures had been implemented, then the tracks on Old Shoreham Road could be built.

I note, in passing, that we could also interpret the Hierarchy completely differently. We could use it to call for the implementation of cycle tracks on Old Shoreham Road with its pre-existing high volume of motor traffic, travelling at higher speeds, because it states that cycle tracks are the necessary solution on roads with high traffic volumes and speeds. In other words, cycle tracks should be built on busy roads as a first principle; we shouldn’t have to wait for other roads to be built as a way to reduce volume, or to wait for the speed limit on the road to be reduced before we start construction.

There is a further, final problem with this claim that the upper principles in the Hierarchy are used to ‘pave the way’ for off-carriageway provision, and to make it possible. Namely that, in reality – in the way the Hierarchy is used in both CTC and DfT guidance – those upper principles are presented as ways of rendering cycle tracks unnecessary. For instance, from LTN 1/12 –

Table 4.2 [a speed/flow diagram] gives an approximate indication of suitable types of provision for cyclists depending on traffic speed and volume. It shows that adopting the upper level solutions in the hierarchy (i.e. reducing the volume and/or speed of traffic) makes on-carriageway provision for cyclists more viable.

I have seen similar claims about the function of the congestion charge in central London; that it has rendered cycle tracks unnecessary because of the reduction in motor traffic. Incidentally, this is a position that the CTC are hoping will prevail on Lambeth Roundabout, in that they have opted for a design that is only suitable for considerably lower motor traffic volume. But we also have the same CTC officer stating that the congestion charge is also making carriageway reallocation for infrastructure possible, just down the road –

the reason TfL was able to remove a lane from Millbank for the 2m wide cycle lane was because traffic volumes were relatively low – ie, measures at the top of the Hierarchy had already been implemented (congestion charging).

We need the Hierarchy to reduce traffic so we can put in infrastructure; but we also need the Hierarchy to reduce traffic so we don’t need to put in infrastructure. So, bizarrely, reductions in traffic volume and speed are presented as ways of enabling cycle tracks to be built, but simultaneously, they are also presented as ways of making cycle tracks unnecessary.

Whether these ambiguities are symptomatic of the Hierarchy itself, or in the way it is able to be interpreted, is probably immaterial. The fact is that the Hierarchy is woefully vague, even downright confusing, and it desperately needs to be updated with guidance that is precise about what kind of provision is necessary on a particular kind of road or street.

If you haven’t already done so, do read Joe Dunckley’s take on the Hierarchy, and David Arditti’s lengthier analysis of CTC policy based on it

I see the principal problem with the HOP being that it is asking for motorists to change their behaviour to facilitate better conditions for cyclists. Turkeys and Christmas springs to mind. One of the old arguments against better infrastructure was “there is no political will”. I suspect there is even less political will to make driving even slower and more awkward – the War Against The Motorist is over dontcha know! Better infrastructure is a win win situation, cyclists are safer and motorists don’t have to worry about killing us!

So am I right in understanding you will have to wait for a decent cycle path until all the car bypasses are finished? If all other measures come first before any cycling provision can be installed, it’s no wonder it takes the UK so long before anything proper is done for cyclists. Pedestrianize London has shown the Dutch hierarchy of roads, an altogether different approach. It’s starting from the need for cycle safety, not from the number of lanes, car traffic or road size: http://pedestrianiselondon.tumblr.com/post/20170547370/cycleway-provision-from-the-experts

Over here in Holland, if any traffic situation seems unsafe, the layout usually is changed to provide safety and ease of use for all road users. But sometimes it may take a very long time: after 30 years, my village finally gets a separate cycle path to the next village, 6 kilometres, 5 million euros and at the cost of quite a number of trees and some front yards. Considering the enormous number of school kids using this road at the same time as the rush hour cars, it’s not a high price to pay. If we would have been dependent on car traffic to decrease, it would never have been built.

+1

and see the latest from Paul James where he plans Twickenham town centre on authentically Dutch lines at:

The Hierarchy of Provision such a confused mess! Like “safety in numbers” nobody really knows what it means. Is it a list to be followed in order, or is it a guide to choose an option?

Why didn’t they just use the Dutch guidelines instead of over-simplifying it into the HoP?

On a related note, I was reading an old post on Vole O’Speed the other night and came across this:

Marttijn Sargentini, the bike cheif in Amsterdam, and thus a very important Dutch traffic planner … told CTC’s Cycle magazine (October 2007): “…Here in Amsterdam we are very clear – for safety, for speed, to give an advantage to the bike, we aim to separate wherever possible.”

Which is the exact opposite of the CTC’s favourite saying: “mix where possible, separate where necessary” (they claim comes from Dutch traffic planning, but I reckon they just made it up)

I notice the Dutch method of segregation usually appears to be an upstand. Would not white line segregation suffice as long as there was sufficient width, continuity and priority across junctions, no obstructions in the cycle path and an even surface – or am I missing something?

I have to say that I have never seen white line segregation anywhere in the Netherlands. In places where there are significant volumes of pedestrians, there will always be kerb separation.

What tends to happen in places where there are much lower volumes of pedestrians (like in the two ‘semi rural’ photographs in this post) is that the ‘pavement’ is simply a wide cycle track, on which pedestrians are perfectly at liberty to walk. In practice pedestrian volume is very low in these locations, because the bicycle is such an obvious choice for trips here, instead of walking. In any case, the track is wide enough, and volume low enough, for there to be little conflict.

My experience of white line segregation in the UK is not good. ‘Discipline’ tends not to be observed. On low volume routes my belief is that there shouldn’t be a white line at all.

I have a copy of the CROW Design manual for bicycle traffic on my desk in front of me. It says “…Another step further is to construct the space reserved for cyclists and that for pedestrians at the same height, seperated by only a sunken kerb or markings” where “space is at a premium”. But this design is not actually shown in any of the diagrams, and in most situations (with exceptions such as road works, and some rural paths with either a solid painted line or no desigated pedestrian space at all) the cycle track and pavement will be seperated with a small kerb.

Something like this?

I’ve always understood the Hierarchy of Provision to be:

1. Provide for cars.

2. Provide for everybody else (except cyclists).

3. Provide for cyclists.

Pingback: A second attempt at the A24 in Morden – and it’s still not good enough | As Easy As Riding A Bike