TfL’s response to the consultation on the route of the Superhighway through Hyde Park was released last week. It reveals, yet again, a curious hostility to cycling from the Royal Parks, the (government) agency that manages the eight Royal Parks in London.

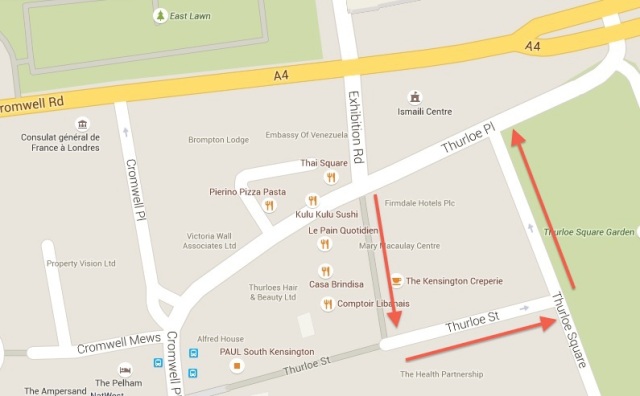

This is the same body that is effectively blocking the most sensible routing of the Superhighway past Buckingham Palace for ‘safety, operational and aesthetic reasons’; that bans cycling along the eastern side of Green Park (yet allows driving, for access); that is apparently reluctant to close parts of Regents Park as through-routes to motor traffic; that organises regular ‘crackdowns’ on cycling, including (notoriously) one last year which saw BBC presenter Jeremy Vine stopped by the Met Police for ‘speeding’ (at 16mph).

The curiousness of the Royal Parks’ position was neatly summed up by City Cyclists back in January –

it seems to me that the [Royal Parks] authority is terribly concerned that building a safe cycle route through this area might lead to conflict with pedestrians. Fair enough. But I don’t see any evidence that The Royal Parks understand that much of that potential ‘conflict’ is because they are trying to squeeze people on foot and bikes into small spaces at junctions that are absolutely mobbed by motor vehicle traffic. The elephant in the room is that there is an awful lot of motor vehicle traffic in the Parks. Why isn’t The Royal Parks worrying about removing some of that, I wonder?

And indeed this latest response from TfL to the consultation reveals that the Royal Parks are still thinking this way. For instance –

3 respondents (<1%), including The Royal Parks, expressed concern about provision for cyclists on North Carriage Drive

The Royal Parks stated that the proposals are not safe enough for pedestrians. Most of these cited potential clashes with cycles due to increased cycle congestion in certain areas of the park

The Royal Parks stated that impact on pedestrians needs to measured and a risk assessment undertaken

Nobody wants to see more conflict between walking and cycling, but it seems to me that the Royal Parks are coming at this issue from a perspective that is bound to see problems where they don’t exist, and fails to diagnose solutions where they can be found.

First of all, from the tone of their comments on this consultation, and other public responses, they appear to have a fairly fixed idea of ‘cycling’ being the preserve of fast, speedy types, posing grave danger to other users, rather than as a potentially universal mode of transport that could be used by all visitors to the Parks. Indeed, these people exist in the Parks already, and they are hardly a great danger to other users.

Ordinary people need safe routes through (and obviously to) the Parks by bike, not just ‘cyclists’, and those routes shouldn’t be compromised because of assumptions about speeding, or bad behaviour, or lycra, or whatever. If there is a genuine issue with bad behaviour, that should be tackled directly, rather than punishing everyone else by not even providing proper routes in the first place.

Secondly, all the (potential) problems with conflict between different users in the parks are almost certainly design problems, rather than any intrinsic problem with cycling itself. Where there are currently issues with ‘speeding’ in Hyde Park, for instance, it’s notable that it is on a desperately narrow shared path, along Rotten Row.

With two-way cycling on the right hand side of that white line, it’s hardly surprising that conflict with walking on the other side of the line is going to occur, with ‘fast’ cyclists seeming to come out of nowhere.

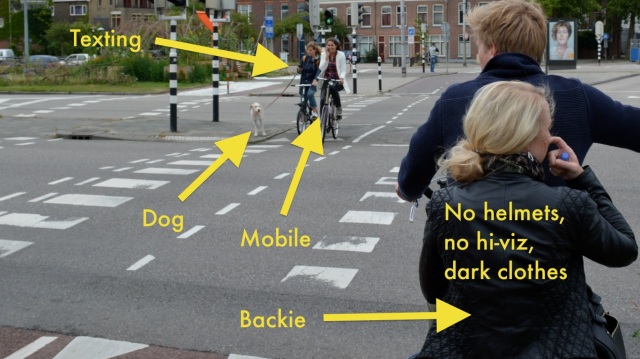

Parks across Europe handle much larger numbers of people cycling, with much less conflict, because their paths are designed to safely accommodate it. In Utrecht –

In Lyon –

And of course in Amsterdam.

And of course in Amsterdam. There isn’t conflict in these parks, precisely because there is enough space allocated to walking and cycling for everyone to get along quite happily. The problems that result from pushing people together into a tiny space isn’t a problem with cycling; it’s a problem with bad design.

There isn’t conflict in these parks, precisely because there is enough space allocated to walking and cycling for everyone to get along quite happily. The problems that result from pushing people together into a tiny space isn’t a problem with cycling; it’s a problem with bad design.

This fixation on the ‘problems’ cycling might cause is even more curious in the light of the Royal Parks’ ambivalence about motor traffic levels in the areas it controls – the Royal Parks maintains at its own expense roads that carry motor traffic through Hyde Park, for instance. We are told that

It is The Royal Parks’ aspiration to reduce the number of motor vehicles in the Royal Parks. It does not feel an immediate ban on cars in Hyde Park is considered feasible given the impact that this would have on those who currently visit by car and taxi.

Reductions in motor traffic would obviously be welcome, but it’s not clear how this is going to be achieved without restrictions on the routes motor traffic can take through the parks. A ‘ban’ on motor traffic needn’t even be a priority in the short term; the main problem with motor traffic in the Parks is how the roads in them are used as through routes. These roads could be converted to access roads, still allowing people to visit by car, but removing the motor traffic using the Parks as a cut-through to somewhere else.

The Royal Parks seem innately conservative; wedded to preserving the status quo, even if that is deeply sub-optimal in terms of safety and convenience, especially for people walking and cycling.

… 300 metres from Three Bridges Primary School

… 300 metres from Three Bridges Primary School